Homing Pigeons Saved Thousands of Lives

Since ancient times, homing pigeons have been utilized for message delivery. The exact nature of their homing instinct remains somewhat mysterious.

It’s speculated that magnetoreception, a biological ability to sense the magnetic field for orientation, plays a role, alongside the pigeon’s capacity to recognize landmarks. Sharp vision and exceptional memory are also believed to contribute, though pigeons are hindered by darkness or poor visibility conditions like fog.

In wartime, messenger pigeons present several benefits. They’re portable, consume minimal food, and can cover distances swiftly. Unlike military dogs, they stay focused on their mission and, if intercepted, reveal no information about their point of origin or intended destination. Averaging speeds of about 90 kilometers per hour across moderate spans, they outpace runners, cyclists, or horseback riders.

Background

Ancient Romans employed pigeons in chariot races to communicate the results to the owners. Genghis Khan set up pigeon relay stations across Asia and much of Eastern Europe, while Charlemagne reserved pigeon-breeding exclusively for the nobility. The Rothschild family’s wealth was reportedly significantly boosted by a pigeon that delivered swift news of the British win at Waterloo. However, it was during the 1870 Siege of Paris that the carrier pigeon truly distinguished itself.

Ypres, Belgium, October 1917. Two unidentified signallers with baskets of carrier pigeons.

Ypres, Belgium, October 1917. Two unidentified signallers with baskets of carrier pigeons.

As the Prussians encircled Paris, the initial strategy of sending dispatches via hollow metal balls along the Seine river turned out to be unreliable. But just six days after the siege commenced on September 19, a balloon named La Ville de Florence released three pigeons at 11 a.m., and by 5 p.m. the same day, they had successfully completed their mission and returned.

Prussian Gunfire

By the time an armistice was declared at the end of January, 409 pigeons had been deployed, with 73 managing to return safely, enduring harsh conditions, Prussian gunfire, and falcons trained for their interception, as detailed by the museum exhibit.

In appreciation, the nation tasked Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, famed for the Statue of Liberty, with creating a bronze monument commemorating the balloonists and pigeons involved in the Siege. Unveiled in 1905 at the Place des Ternes in Paris, this monument was unfortunately melted down during World War II.

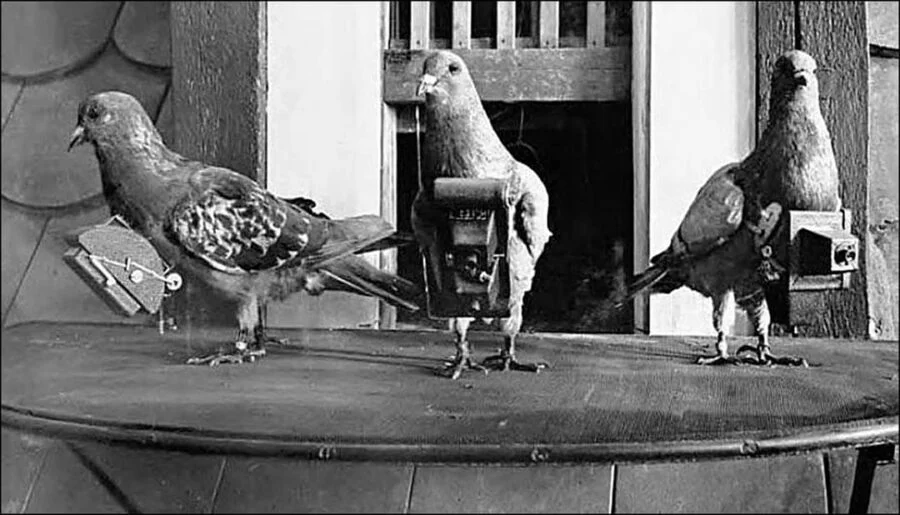

By the onset of World War I, French pigeon lofts were fully operational, as were those of other nations involved in the conflict. The Germans utilized pigeons equipped with cameras, an innovative method superseded only with the advent of aerial reconnaissance aircraft. By the war’s conclusion, France had enlisted the service of 30,000 pigeons, imposing severe penalties, even death, for hindering their missions.

Homing Pigeons and the Dickin Medal

Homing pigeons have been pivotal in warfare, valued for their ability to reliably return home, their swiftness, and their high-flying capabilities, making them ideal for delivering military messages. Specifically, the Racing Homer breed was instrumental during both World Wars, with 32 of these pigeons being honored with the prestigious Dickin Medal.

The PDSA Dickin Medal was instituted in 1943 in the United Kingdom by Maria Dickin to honour the work of animals in World War II.

The PDSA Dickin Medal was instituted in 1943 in the United Kingdom by Maria Dickin to honour the work of animals in World War II.

Additionally, accolades like the Croix de Guerre were bestowed upon pigeons such as Cher Ami, while the Dickin Medal was also awarded to G.I. Joe and Paddy, recognizing their extraordinary contributions to saving lives during these conflicts.

In the world wars, these carrier pigeons were tasked with ferrying messages back to their home coops positioned behind the battle lines. Upon their return, the coop’s integrated wires would trigger an alert system, notifying Signal Corps soldiers that a message had arrived. These soldiers would then retrieve the message from the pigeon’s canister and ensure its prompt delivery through telegraph, field phone, or direct messenger.

Serving as a carrier pigeon was fraught with peril, as enemy combatants frequently attempted to shoot the birds down, aware of their role in transmitting critical intelligence. Despite these dangers, some pigeons achieved legendary status among the troops they served. For instance, a pigeon named Spike completed 52 missions unscathed.

Homing Pigeons at Sea

Pigeons found successful applications on both aircraft and ships, yet they were predominantly utilized by the British Expeditionary Force for conveying messages from front-line trenches or advancing units, overseen by the Directorate of Army Signals.

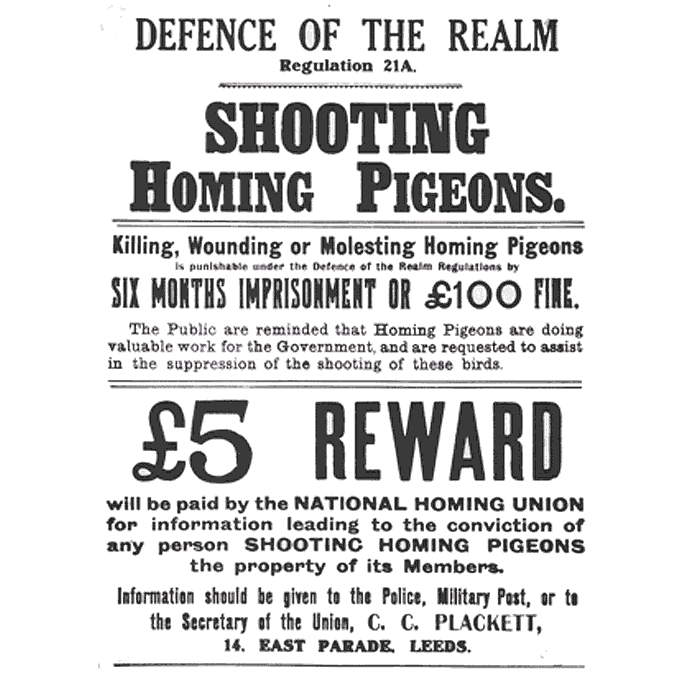

WWI poster produced by the UK Government

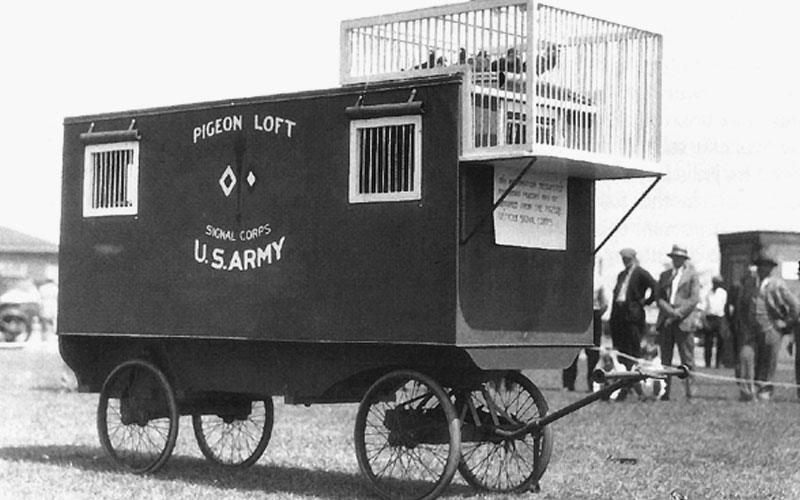

WWI poster produced by the UK GovernmentThese birds homed to both stationary and mobile lofts, returning with crucial communiqués. Fixed lofts were set up in various structures like outbuildings or rooftops, while in the field, tailored wooden sheds were constructed.

Mobile lofts, either horse-drawn or motorized, were deployed where fixed ones were impractical. These could be relocated as needed once pigeons had acclimatized to their new base. The pigeons underwent meticulous training and care, being fed only once daily shortly before sunset, and withheld food for at least 24 hours post-departure from the loft. Release times were cautiously chosen to ensure optimal navigational conditions, avoiding dusk, dawn, or foggy weather.

To ensure message redundancy, communiqués were dispatched with two birds released a minute apart, avoiding the simultaneous release of male and female pigeons. In cases of highly confidential messages, encryption was employed, mindful that pigeons might fall into enemy hands. Both the message’s destination and the origin were encoded to maintain secrecy and security.

Homing Pigeons in WW1

During World War I, homing pigeons played a crucial role in communications. In the pivotal 1914 First Battle of the Marne, the French military deployed 72 pigeon lofts alongside their advancing troops. Similarly, the US Army Signal Corps employed 600 pigeons in France for message delivery tasks.

Belgian Monument in Honor of Carrier Pigeons during 1914-1918

Belgian Monument in Honor of Carrier Pigeons during 1914-1918

One notable pigeon, a Blue Check cock named Cher Ami, was decorated with the French “Croix de Guerre with Palm” for his valiant efforts in transmitting 12 vital messages throughout the Battle of Verdun.

In his final mission in October 1918, despite being injured by gunfire, he succeeded in delivering a message that was instrumental in saving the lives of 194 soldiers from the 77th Infantry Division’s “Lost Battalion”. The life-saving note was discovered in a capsule attached to what remained of his leg.

54,000 War Homing Pigeons

The United States Army Pigeon Service, also known as the Signal Pigeon Corps, was a dedicated division of the U.S. Army operational in both World Wars. Their primary role was to oversee the training and deployment of homing pigeons for communications and reconnaissance tasks.

In World War II, this unit expanded to include 3,150 soldiers and a remarkable roster of 54,000 war pigeons. These pigeons were valued for their stealthy, reliable means of sending messages, with over 90% of communications dispatched by them successfully received.

The Pigeon Loft at Rampont, France.

The Pigeon Loft at Rampont, France.

The pivotal facility for the U.S. Army’s pigeon operations, the Pigeon Breeding and Training Center, was stationed at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, from 1917 to 1943 and then from 1946 to 1957. A relocation occurred from October 1943 to June 1946 when the center moved to Camp Crowder.

The practice of employing pigeons for military communication ceased in 1957. Following their decommission, fifteen pigeons distinguished for their service were donated to zoos, while approximately a thousand others were sold off to private individuals.

Stockpile of 1,508 Birds

The United States Navy, operating in France, managed 12 pigeon stations with a stockpile of 1,508 birds by the war’s conclusion. These pigeons were often brought aboard aircraft to swiftly convey messages back to these bases, participating in a total of 10,995 wartime aircraft patrols.

During these missions, 829 pigeons were released from aircraft; the crew had to carefully launch the birds either upwards or downwards, considering the aircraft’s design, to avoid the propellers and prevent the birds from being swept into the wings or struts. Out of these releases, only 11 pigeons went missing, while the rest succeeded in delivering their 219 messages effectively.

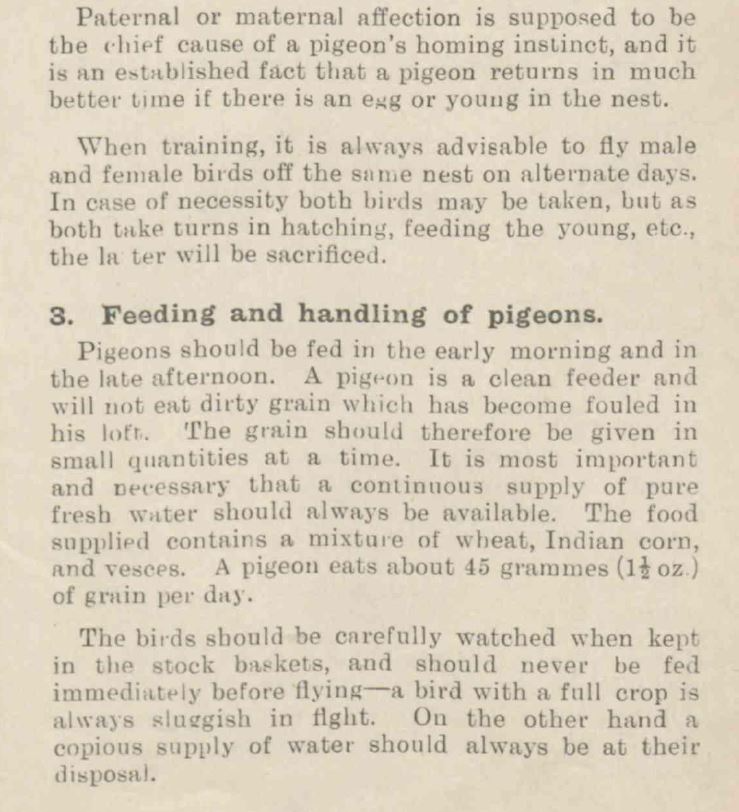

While pigeons naturally possess the homing instinct to return to their loft, refining this ability into an effective wartime communication tool required specialized training.

While pigeons naturally possess the homing instinct to return to their loft, refining this ability into an effective wartime communication tool required specialized training.

Pigeons were deemed a crucial component of naval aviation communications, evidenced by the inclusion of a pigeon house on the stern of the USS Langley, the first United States aircraft carrier, when it was commissioned on March 20, 1922. These pigeons underwent training at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard during the period Langley was being refitted.

While individual pigeons reliably returned to the ship when released in small numbers for exercise, an incident occurred where the entire flock was released while the Langley was anchored off Tangier Island. Instead of returning, the pigeons headed south and settled in the cranes at the Norfolk shipyard. Following this event, the pigeons were not taken to sea again.

President Wilson the Legend of Homing Pigeons

Originating from France, President Wilson, a homing pigeon, was initially designated to the U.S. Army’s nascent Tank Corps. His first combat experience involved carrying messages for the 326th and 327th Tank Battalions, which were under the command of Colonel George S. Patton during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel.

Stationed with the squad at the forefront of the advance, he was dispatched from a tank’s turret to relay the positions of enemy machine gun placements, enabling artillery strikes ahead of the infantry’s progression.

Pigeons underwent training to traverse open waters, a behavior typical for seabirds like gulls or albatrosses but unnatural for pigeons. This capability enabled their use on aircraft, allowing them to relay the positions of downed crews when alternative communication methods were compromised.

Pigeons underwent training to traverse open waters, a behavior typical for seabirds like gulls or albatrosses but unnatural for pigeons. This capability enabled their use on aircraft, allowing them to relay the positions of downed crews when alternative communication methods were compromised.

Subsequent to this engagement, President Wilson was attached to an infantry squad from the 78th Division, engaged in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive near Grandpré, France. On the morning of October 5, 1918, his unit was embroiled in a fierce battle. Released to summon artillery support, President Wilson embarked on his journey back to his loft at Rampont, located forty kilometers away.

Read More The V-3 Super Cannon Could Hit London from France

His flight drew the hostile attention of German troops, who unleashed a dense barrage of bullets in his direction. Nevertheless, he succeeded in conveying the critical message within twenty-five minutes, albeit arriving with severe injuries; he had lost his left leg, and sustained a significant wound to his chest.

Miraculously surviving these injuries, President Wilson was subsequently taken to the U.S. Army Signal Corps Breeding and Training Center for recovery. He lived out his days there, passing away in 1929, leaving behind a legacy of bravery and an indelible mark on military avian service.

USA Signal Pigeon Corps

At the onset of World War II, the U.S. Army’s Signal Pigeon Corps was operational with around 54,000 pigeons. The increasing reliance on these pigeons necessitated the establishment of a dedicated unit within the U.S. Army Veterinary Service.

This unit was tasked with ensuring pigeon health, maintaining their physical performance, and preventing the spread of pigeon-related diseases that could affect other animals and humans.

A messenger pigeon being released from a port hole in the side of a British Mark V tank of the 10th Battalion, Tank Corps. Photograph taken near Albert, France on the 9th August 1918 during the Battle of Amiens.

A messenger pigeon being released from a port hole in the side of a British Mark V tank of the 10th Battalion, Tank Corps. Photograph taken near Albert, France on the 9th August 1918 during the Battle of Amiens.

The unit achieved its goals by providing expert services and guidance in managing the pigeons’ care, nutrition, accommodation, and transportation. It also carried out lab diagnostics and research on pigeon ailments, implemented disease control measures through quarantine, conducted health inspections, and offered expertise in training pigeon handlers.

Army Veterinary Service

Despite deploying 36,000 pigeons abroad, the implementation of these veterinary services varied across different theaters and overseas locations, given the novelty of integrating military veterinary practices for pigeon services at the time.

Among the various health-related concerns addressed by the Army Veterinary Service, the supply and quality of feed, along with the pigeons’ housing, stood out. Optimal nutrition and feeding practices were crucial for the pigeons’ health and directly influenced their homing capabilities.

The Signal Corps was responsible for sourcing the feed, which often arrived in overseas locations in subpar condition—compromised by improper handling, pest infestation, or exposure to moisture, leading to spoilage or contamination.

“Under favourable conditions a carrier pigeon can cover a distance of 15-200 miles at an average air speed of 30 miles per hour. To get the best out of him he must be conditioned as carefully as a greyhound, and be trained along the line of flight over which it is intended to use him“.

“Under favourable conditions a carrier pigeon can cover a distance of 15-200 miles at an average air speed of 30 miles per hour. To get the best out of him he must be conditioned as carefully as a greyhound, and be trained along the line of flight over which it is intended to use him“.

Adequate shelter was another significant issue, especially for units stationed abroad. Standardized loft designs from the U.S. were sometimes modified to adapt to the diverse and changing weather conditions, particularly in the Central Pacific Area, leading to the construction of open-front lofts.

Key considerations for these accommodations included exposure to sunlight, ensuring dryness, maintaining a draft-free environment, and upholding strict sanitation standards to optimize the health and efficiency of the signal pigeons.

Homing Pigeons

During World War II, the United Kingdom utilized approximately 250,000 homing pigeons for various critical tasks, including facilitating communication with operatives such as the Belgian spy Jozef Raskin who were stationed behind enemy lines.

Notably, 32 of these pigeons were honored with the Dickin Medal, the most prestigious award for animal bravery, recognizing distinguished pigeons like the United States Army Pigeon Service’s G.I. Joe and the Irish pigeon named Paddy.

Throughout the war, the UK’s Air Ministry Pigeon Section was operational, extending a little while post-war. The utilization of pigeons in military operations was overseen by a specialized Pigeon Policy Committee.

In 1945, the head of this section, Lea Rayner, suggested the innovative yet controversial idea of training pigeons to carry small explosives or biological weapons to specific targets. Despite the potential, this proposal was not pursued by the committee. By 1948, the UK’s military formally acknowledged that pigeons no longer held any utility for their operations.

Messages transmitted via pigeon were secure from eavesdropping by enemy operatives, offering a reliable alternative when technological means failed.

Messages transmitted via pigeon were secure from eavesdropping by enemy operatives, offering a reliable alternative when technological means failed.

During wartime, messenger pigeons were allotted a special provision of corn and seeds. However, this allowance was revoked at war’s end, compelling pigeon keepers to use their personal rations of corn and seeds to feed the birds. Despite their diminished role post-war, the UK’s MI5 maintained a vigil over the potential use of pigeons by adversarial forces.

Up until 1950, they supported a program where 100 pigeons were kept by a civilian pigeon fancier, staying prepared for any possible use of pigeons by enemy agents. This cautious stance toward pigeon-based communication persisted long after the war, although the Swiss army didn’t disband its pigeon section until 1996.

William of Orange Market Garden

The British paratroopers, equipped with the same radios they had used two years prior in North Africa, faced unforeseen challenges in Arnhem. While these radios were adequate in the vast, open desert, they proved ineffective in the dense, urban, and forested landscape of Arnhem, resulting in a complete communication blackout.

One of the most famous pigeons of World War II is known as William of Orange.

One of the most famous pigeons of World War II is known as William of Orange.

This failure in communication led to significant operational issues. Army units were isolated, unable to coordinate with each other or report back to General Urquhart’s division headquarters in Oosterbeek.

Moreover, during the crucial initial days of the Battle of Arnhem, General Urquhart found himself cut off, unable to relay the critical situation of his troops to the British army command in Nijmegen or to the higher-ups in London.

High Command in London

The lack of radio transmissions from Arnhem at the battle’s onset alarmed the High Command in London, prompting them to deduce a malfunction with the communication equipment. In response, reconnaissance flights were dispatched, with Spitfires photographing the Arnhem area.

An aluminum PG-14 message holder for attachment to a war pigeon’s leg, U.S. Army Signal Corps, World War I. 1 x 2.9 cm, 1.7 gm

An aluminum PG-14 message holder for attachment to a war pigeon’s leg, U.S. Army Signal Corps, World War I. 1 x 2.9 cm, 1.7 gm

One notable photograph capturing the aftermath of destroyed German armored vehicles near the Rhine Bridge was taken during these missions, hinting to the British High Command that the operation was not proceeding as planned. However, the full extent of the dire situation was not immediately grasped in London.

The turning point came on Tuesday, September 19, 1944, when London received a critical update through a homing pigeon named William of Orange. This pigeon, along with others, was brought into Arnhem by John Frost’s troops. Encircled by German forces and with radio communications to Oosterbeek severed, Frost resorted to releasing William of Orange to deliver the urgent message, marking a significant moment in the battle’s communication efforts.

John Frost

William of Orange carried a crucial note strapped to his leg, detailing that Frost’s troops were holding the northern ramp of the bridge but were isolated from the main British forces, urgently requiring air support to sustain their defense against German forces.

Launching his pivotal journey at 10:30 am, William of Orange arrived at his loft in Cheshire, England, by 2:55 pm, covering a remarkable distance of 400 kilometers in just 4 hours and 25 minutes, a feat hailed by Stewart Wardrop of the Royal Racing Pigeon Association as an exceptional record.

Wardrop, in his statement to the Daily Mail, emphasized the pigeon’s extraordinary feat, considering the challenging circumstances of being confined in a cage for days, released amidst enemy gunfire, and navigating 200 kilometers over open sea to England.

Men from the 1st Airborne Division fighting during Operation Market Garden Arnhem, September 1944.

Men from the 1st Airborne Division fighting during Operation Market Garden Arnhem, September 1944.

Releasing the pigeon was fraught with challenges; amidst enemy fire, a British paratrooper attempted to send him on his way under the Rhine Bridge’s ramp. Initially hesitant, the pigeon lingered nearby until a British soldier’s warning shots prompted him to commence his critical flight to England.

Homing Pigeons Mission Complete

The reception of the message significantly alerted the British High Command to the dire situation in Arnhem. Regrettably, adverse weather conditions thwarted the air support Frost’s troops desperately needed. It’s noteworthy that on September 19, British forces in Oosterbeek finally established a tentative, though unreliable, radio link with the allied headquarters at Groesbeek.

While Frost’s troops released more pigeons, William of Orange stood out for successfully completing the journey back to England, the only one known to have done so.

For his outstanding service, William of Orange was honored with the Dickin Medal, regarded as the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross. He became the 21st recipient of this accolade, instituted in 1943 by the compassionate Mrs. M. E. Dickin, founder of the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals. His awarded medal bore the inscription ‘For Gallantry, We also serve.’

Post-war, William of Orange lived for another decade, having been purchased by a pigeon fancier for 135 British pounds, commemorating a legacy of bravery and steadfast duty.

Homing Pigeons Australia

In 1942, amidst growing concerns over a potential Japanese invasion of Australia, the predominant modes of communication were line and wireless. However, a collaborative meeting between civilian pigeon enthusiasts and senior army signal officers explored pigeons as an alternative communication method.

The successful trial led to the establishment of the Australian Corps of Signals Pigeon Service, predominantly staffed by former civilian pigeon fanciers now in the army. Following a nationwide call, over 13,500 homing pigeons were contributed to the service.

Torokina, Bougainville Island. 1945. Mobile loft used to train young message carrying pigeons.

Torokina, Bougainville Island. 1945. Mobile loft used to train young message carrying pigeons.

Initially, this service facilitated messages between Australia’s coastal defenses, later extending to Voluntary Defence Corps posts, coast-watching stations, and aircraft-spotting locations. The operation expanded to jungle regions, but the challenging climate in New Guinea affected the pigeons adversely, prompting the setup of local army breeding lofts.

This strategy aimed to acclimate pigeons to the environment where they would serve. Various locations in New Guinea, including Tarakan, Laubuan, Morotai, Bougainville, and New Britain, hosted pigeon sections.

To ensure comprehensive training, pigeon lofts were integrated with signal schools, infantry training, and water transport training facilities, enabling military personnel to learn pigeon care.

Unsung heroes of war

Unsung heroes of war

The diet for these pigeons included maple peas, wheat, unpolished rice, canary seed, linseed, Milo, and hulled oats, and they were regularly treated with DDT to fend off feather lice, a prevalent issue in the tropics.

Pigeons faced formidable flying conditions in New Guinea, with the region’s mountainous terrain, frequent tropical rains, and mists posing significant challenges. Despite these obstacles, messenger pigeons were upheld as a vital and effective communication resource.

Pigeons to Secured Artillery Support

Blue Bar Cock Pigeon No. 139 was honored with the prestigious Dickin Medal for his act of bravery during a hazardous flight through a severe tropical storm near Madang, New Guinea, on July 12, 1945.

Stationed with Detachment 55 Port Craft Company in Madang, this pigeon heroically transported a distress message from a boat in trouble, covering a distance of 40 miles (64 km) in just 50 minutes. The conveyed message was a crucial call for help, detailing the boat’s dire situation, being washed onto the beach at Wadau under heavy seas and quickly filling with sand, necessitating immediate assistance.

The bird’s timely delivery of the message facilitated the rescue and salvage operation, saving the boat along with its critical cargo of stores, ammunition, and equipment. Prior to this mission, the pigeon had successfully executed 23 operational flights, covering a cumulative distance of 1,004 miles.

Some were fitted with tiny cameras and dispatched by soldiers.

Some were fitted with tiny cameras and dispatched by soldiers.

The Dickin Medal was awarded to this gallant pigeon in February 1947, with the citation highlighting its remarkable journey from the stranded Army boat 1402 on Wadou Beach back to Madang, facilitating a timely rescue that saved both the vessel and its significant load.

Military Cross

Captain Stuart McDonald’s company also owed their gratitude to homing pigeons for their invaluable service during World War II. On July 2, 1945, while stationed on Bougainville, Captain McDonald’s company was engaged in establishing a base by the Mivo River.

They encountered an unexpected enemy force of around one hundred. Isolated and under continuous fire, with their communication lines severed, the company was in a precarious situation.

In a critical move, on the third day, they dispatched their two pigeons with a request for artillery support in five hours. The successful message delivery led to “Under favourable conditions a carrier pigeon can cover a distance of 15-200 miles at an average air speed of 30 miles per hour. To get the best out of him he must be conditioned as carefully as a greyhound, and be trained along the line of flight over which it is intended to use him“. For his leadership and the successful use of pigeons to secure artillery support during the Mivo River engagement from July 2 to 5, 1945, Captain McDonald was awarded the Military Cross

News

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering Perched precariously on the cliffs of Mount Heng in Shanxi Province, China, the Hanging Temple, also known as Xuankong Temple, Hengshan Hanging Temple, or Hanging Monastery, is an architectural…

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets The “Willendorf Venus” stands as one of the most revered archaeological treasures from the Upper Paleolithic era. Discovered in 1908 by scientist Johann Veran near Willendorf, Austria, this small yet profound…

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts New archaeological research has uncovered intriguing insights into the ritual practices of the ancient Maya civilization. The focus of this study is a ceremonial offering found beneath the sediment…

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins The history of agricultural innovation is a fascinating journey that spans thousands of years, and one of the earliest known agricultural machines is the threshing sledge. Recently, a groundbreaking study…

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits In a remarkable discovery that has captured the attention of archaeologists and historians alike, a 7.5-foot-long iron sword was unearthed from a 1,600-year-old burial mound in Nara, Japan. This oversized weapon,…

The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots

Experimental The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots The Inflatoplane from Goodyear was an unconventional aircraft developed by the Goodyear Aircraft Company, a branch of the renowned Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, also famed for the Goodyear…

End of content

No more pages to load