U-118 – An Unexpected Visitor to the Shores of Hastings

The World War I era marked a profound shift in the mechanics of warfare. This period saw the advent of submarines, changing the landscape of naval warfare forever. Among these submarines, the German U-boat, U-118, holds a distinctive place.

Its tale is not confined to its military exploits but extends to an intriguing post-war narrative when it unexpectedly washed ashore on the beach in Hastings, Sussex.

An aerial view of U-118 on the beach. Giving a great sense of the scale of the machine.

An aerial view of U-118 on the beach. Giving a great sense of the scale of the machine.

U-118

Commissioned during the height of World War I, U-118 was a Type UE II mine-laying submarine. Its prime function was to disrupt enemy navigation by planting mines in their shipping routes.

However, its active service was cut short by the end of the war, leaving its combat potential largely untested.

From Surrender To Unplanned Journey

With the armistice inked on November 11, 1918, the hostilities ceased. U-118, like all German U-boats, was surrendered to the Allies and was intended to be towed to France for scrapping.

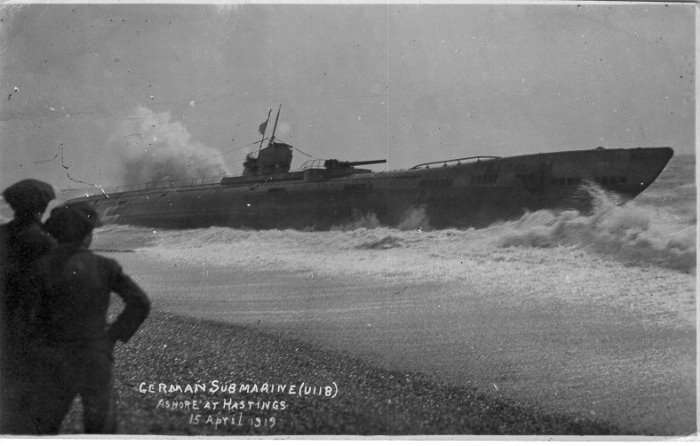

U-118 recieving a battering from the choppy weather.

U-118 recieving a battering from the choppy weather.

But the U-boat’s fate took an unexpected turn when a storm severed the tow lines, leading to U-118 running aground on Hastings beach on April 15, 1919. Despite numerous attempts, the authorities failed to refloat the submarine.

An Unlikely Tourist Attraction

The stranding of U-118 on Hastings beach presented a rare spectacle for locals and visitors alike. During this time, submarines were largely unfamiliar to the general public, making the stranded U-boat an object of curiosity and wonder.

The war’s end was still a fresh memory, and U-118, stranded on a peaceful beach, served as a stark contrast to the recent past and a unique diversion for the war-weary public.

People from all walks of life, intrigued by this rare opportunity, flocked to Hastings.

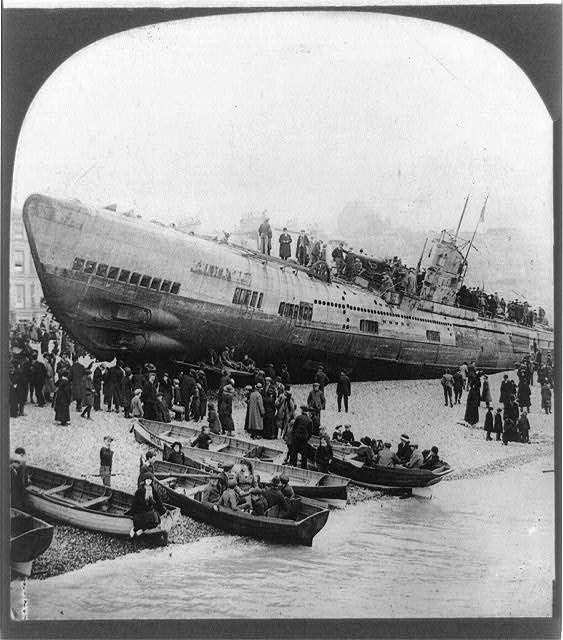

Tourists all over U-118.

Tourists all over U-118.The local economy, sensing a commercial opportunity, leveraged this situation to their advantage. Sightseers were charged a fee for a tour inside the U-boat, offering many a unique chance to witness the internal workings of this naval marvel.

Images of U-boat found their way onto newspapers and postcards, amplifying national and international interest in the beached submarine.

This situation lasted several months, providing an unexpected source of revenue for Hastings and offering the British public an unprecedented form of entertainment.

The Demise of U-118

Chief Boatman William Heard and Chief Officer W. Moore, both part of the coast guard, were in charge of giving interior tours of the submarine to important guests. However, by the end of April, these tours came to a sudden halt when the two men fell critically sick.

Initial suspicions pointed towards spoiled food on the submarine as the cause, but the health of both men progressively deteriorated. Moore succumbed to his illness in December 1919, and Heard passed away in February 1920.

An investigation concluded that lethal gas, possibly chlorine from the submarine’s damaged batteries, had resulted in lung and brain abscesses in the men.

Even though interior tours were discontinued, tourists continued to flock to the site to have their pictures taken on or beside the U-boat’s deck.

Another great image showing the size of U-118.

Another great image showing the size of U-118.

The decision to dismantle the submarine was made to resolve the issues it posed. The process, beginning in December 1919, took over two months of meticulous labor.

By the end of this process, the submarine was reduced to scrap, leaving behind no trace of the war machine that had once been the centre of public fascination.

News

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering Perched precariously on the cliffs of Mount Heng in Shanxi Province, China, the Hanging Temple, also known as Xuankong Temple, Hengshan Hanging Temple, or Hanging Monastery, is an architectural…

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets The “Willendorf Venus” stands as one of the most revered archaeological treasures from the Upper Paleolithic era. Discovered in 1908 by scientist Johann Veran near Willendorf, Austria, this small yet profound…

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts New archaeological research has uncovered intriguing insights into the ritual practices of the ancient Maya civilization. The focus of this study is a ceremonial offering found beneath the sediment…

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins The history of agricultural innovation is a fascinating journey that spans thousands of years, and one of the earliest known agricultural machines is the threshing sledge. Recently, a groundbreaking study…

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits In a remarkable discovery that has captured the attention of archaeologists and historians alike, a 7.5-foot-long iron sword was unearthed from a 1,600-year-old burial mound in Nara, Japan. This oversized weapon,…

The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots

Experimental The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots The Inflatoplane from Goodyear was an unconventional aircraft developed by the Goodyear Aircraft Company, a branch of the renowned Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, also famed for the Goodyear…

End of content

No more pages to load