Westland Whirlwind Most Heavily Armed Tank Buster

The Westland Whirlwind, twin-engine, single-seat fighter could have revolutionized aerial combat. Manufactured by a modest-sized company in southwest England, this aircraft appeared as an extremely formidable force.

Its nose was equipped with four tightly-clustered 20mm cannons capable of destroying a tank—something no other aircraft of its time could achieve.

Additionally, it boasted several innovative features, such as a bubble canopy, air intakes on the wing’s leading edges, slats, and Fowler flaps.

The aircraft featured a slab-sided fuselage over the wing, an optimal design for reducing high-speed interference drag. When it made its initial flight on October 11, 1938, the Whirlwind was considered the fastest and most heavily armed fighter in the world.

Background

By the mid-1930s, the evolving pace of aerial combat led aircraft designers worldwide to recognize that faster attack speeds were reducing the time pilots had to fire at targets.

This decrease in engagement time meant less ammunition could hit and effectively destroy a target. Instead of the typical two rifle-caliber machine guns, the need for six or eight became evident; studies demonstrated that eight machine guns could unleash 256 rounds per second.

First P9 Whirlwind prototype L6844 at Yeovil 1938. All Dark Grey paint scheme

First P9 Whirlwind prototype L6844 at Yeovil 1938. All Dark Grey paint scheme

However, the eight machine guns on the Hurricane, firing rifle-caliber rounds, were not sufficiently powerful to quickly disable an opponent, especially at ranges other than their optimal firing alignment. The emergence of cannons, like the French 20 mm Hispano-Suiza HS.404 capable of firing explosive rounds, shifted focus toward aircraft designs that could accommodate four cannons.

Although the most nimble fighters were typically small and light, their limited fuel capacity confined them to defensive and interception missions. In contrast, the larger airframes and greater fuel capacities of twin-engine designs were preferred for long-range offensive operations.

The first British specification for a high-performance machine-gun monoplane came with the Air Ministry specification F.5/34 for a radial-engined fighter suitable for tropical conditions, which led to four aircraft designs, though these were soon eclipsed by advancements in the new Hawker and Supermarine fighters.

By 1935, recognizing the need for a cannon-armed experimental aircraft, the RAF Air Staff issued specification F.37/35, calling for a single-seat day and night fighter armed with four cannons and capable of exceeding the speed of contemporary bombers by at least 40 mph (64 km/h), reaching speeds of at least 330 mph (530 km/h) at 15,000 ft (4,600 m).

Plenty of Designs Were Rolling In

In response to this specification, eight designs from five companies were proposed. Boulton Paul presented the P.88A and P.88B, single-engine designs differing by their engines: Bristol Hercules radial or Rolls-Royce Vulture inline. Bristol submitted the Type 153, a single-engined design with wing-mounted cannons, and the Type 153A, a twin-engined variant with nose-mounted cannons.

Whirlwind HE-V P6969 of No. 263 Squadron RAF, Exeter, February 1941

Whirlwind HE-V P6969 of No. 263 Squadron RAF, Exeter, February 1941

Hawker proposed a Hurricane variant, Supermarine offered the Type 312, a variant of its Spitfire, and the Type 313, a twin-engined design (using either Rolls-Royce Goshawk or Hispano 12Y engines) with four nose-mounted guns and potential additional armament firing through the propeller hubs if the 12T was used. Lastly, the Westland P.9 featured two Rolls-Royce Kestrel K.26 engines and a twin tail.

By May 1936 the Debate Was Changing

In May 1936, when the aircraft designs were evaluated, there was a debate about the maneuverability of twin-engine designs compared to single-engine ones, and concerns about the accuracy of cannon fire from wing-mounted guns due to uneven recoil.

The conference ultimately recommended the twin-engine approach with nose-mounted cannons, favoring the Supermarine 313. Despite Supermarine’s proven track record with fast aircraft, exemplified by the then-under-trial Spitfire, they, along with Hawker, were unable to quickly adapt their single-engine designs, needing over two years for modifications.

Consequently, Westland, which was less burdened and more advanced in their project, was selected to proceed along with the P.88 and the Type 313.

When targeting railways, the Whirlwind’s four 20 mm Hispano cannons were highly effective. Indeed, one pilot from No. 137 Squadron destroyed four locomotives in a single mission. In their first six months of fighter-bomber operations, No. 137 Squadron hit thirty-seven goods trains, sixteen at night and the rest during daylight.

When targeting railways, the Whirlwind’s four 20 mm Hispano cannons were highly effective. Indeed, one pilot from No. 137 Squadron destroyed four locomotives in a single mission. In their first six months of fighter-bomber operations, No. 137 Squadron hit thirty-seven goods trains, sixteen at night and the rest during daylight.

A contract for two Westland P.9s was issued in February 1937, with expectations of them flying by mid-1938. Orders for the P.88s and a Supermarine design were placed in December, but both were canceled by January.

Under the leadership of W. E. W. “Teddy” Petter, the Westland design team crafted an aircraft featuring advanced technology.

The aircraft had a tubular monocoque fuselage with a T-tail, a design adaptation from an originally planned twin tail, which was abandoned due to turbulence caused by large Fowler flaps. The T-tail configuration moved the elevator out of the disturbed air flow when flaps were deployed.

The outer wings and radiator openings were equipped with Handley Page slats connected by duraluminum torque tubes. These slats were permanently closed in June 1941 following two crash incidents during aggressive maneuvers, leading to improved flight characteristics without affecting take-off and landing performance.

Rolls-Royce Kestrel K.26

The aircraft’s engines, based on the Rolls-Royce Kestrel K.26 and later named Peregrine, were initially integrated with long exhaust ducts routed through the wings and fuel tanks.

This setup was revised to external exhausts after a malfunction nearly caused a loss of control. Cooling was managed by ducted radiators embedded in the wing’s leading edges to minimize drag.

It was powered by two Rolls-Royce Kestrel V-12 engines, which were among the most advanced aero engines available during the mid-1930s.

It was powered by two Rolls-Royce Kestrel V-12 engines, which were among the most advanced aero engines available during the mid-1930s.

Constructed mainly from stressed-skin duralumin and a magnesium alloy in the rear fuselage, the aircraft featured one of the world’s first full bubble canopies, providing the pilot with excellent visibility, except directly over the nose.

Armed with four 20 mm cannons in the nose, the aircraft boasted a firing rate of 600 lb/minute, making it one of the most heavily armed fighters of its time. The centralized weapon arrangement eliminated the convergence issues common with wing-mounted guns.

Despite its extensive secrecy during development, details of the aircraft had already surfaced in the French press, highlighting the high expectations surrounding its performance.

L6844, the first prototype, took to the skies on October 11, 1938. Its construction had been postponed primarily due to the integration of new features and was further delayed by the late arrival of the engines and undercarriage components.

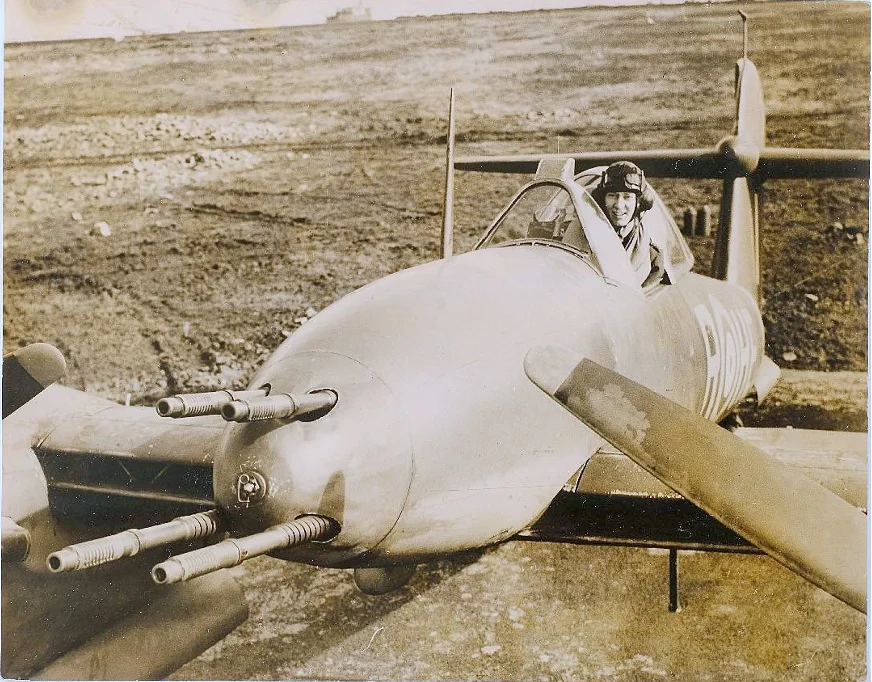

Chief test pilot of Westland, Harald Penrose flying one of the last production Whirlwinds P7110.

Chief test pilot of Westland, Harald Penrose flying one of the last production Whirlwinds P7110.

By the end of that year, L6844 was transferred to RAE Farnborough, with additional service trials later conducted at Martlesham Heath.

The Whirlwind demonstrated outstanding handling qualities and was remarkably easy to pilot across a range of speeds. However, it faced issues with inadequate directional control during take-off, which led to the decision to enlarge the rudder area above the tailplane.

Westland Whirlwind was Fast

The Whirlwind was relatively compact, only slightly larger than the Hurricane, yet it boasted a smaller frontal area. Its landing gear was fully retractable, contributing to the aircraft’s sleek, streamlined appearance with minimal openings or protrusions

Unlike many designs that positioned radiators beneath the engines, the Whirlwind’s were integrated into the leading edges of the inner wings, a feature that unfortunately led to overheating issues. Powered by two 885 hp (660 kW) Peregrine engines, the Whirlwind reached speeds over 360 mph (580 km/h), matching the pace of contemporary single-engine fighters.

However, its operational range was limited, with a combat radius under 300 miles (480 km), making its effectiveness as an escort comparable to that of the Hurricane and Spitfire. The initial delivery of Peregrine engines to Westland didn’t occur until January 1940.

Rare picture of a Westland Whirlwind with the nose section removed showing its 4×20 mm Hispano-Suiza HS.404 cannons.

Rare picture of a Westland Whirlwind with the nose section removed showing its 4×20 mm Hispano-Suiza HS.404 cannons.

By late 1940, with the Spitfire set to be equipped with 20 mm cannons, the unique selling point of the Whirlwind’s armament was diminishing.

Furthermore, as RAF Bomber Command shifted towards night operations, the demand for escort fighters decreased, shifting focus to attributes like range and carrying capacity for large radar systems—areas where the Bristol Beaufighter was proving as capable, if not superior, to the Whirlwind.

Westland Whirlwind Only 112 Were Built

Production was dependent on the success of its test program; though the Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (ACAS) was impressed, the design’s experimental nature warranted thorough testing. Over 250 modifications to the prototypes delayed an initial production order for 200 aircraft until January 1939, with a subsequent batch planned, and deliveries to fighter squadrons expected to commence in September 1940.

Earlier considerations had proposed production by other firms, such as Fairey or Hawker, and a plan in early 1939 to produce 800 units at the Castle Bromwich factory was abandoned in favor of Spitfire production, leaving Westland to build an additional 200.

Westland Whirlwind P6974 HE-M August 1942

Westland Whirlwind P6974 HE-M August 1942

Despite its potential, production of the Whirlwind ceased in January 1942 after only 112 units were built, along with the two prototypes. Rolls-Royce shifted its focus to the Merlin and the problematic Vulture engines rather than the Peregrine.

Given that the Whirlwind was specifically designed around the Peregrine engine, adapting it to use a larger engine would require significant redesign.

Following the discontinuation of the Westland Whirlwind, Petter advocated for the development of a Whirlwind Mk II, envisioned with an upgraded 1,010 hp (750 kW) Peregrine engine featuring an enhanced supercharger for better high-altitude performance and the use of 100 octane fuel for increased boost.

However, this plan was ultimately scrapped when Rolls-Royce halted work on the Peregrine. Notably, manufacturing a Whirlwind required three times as much alloy as a Spitfire, adding to its production challenges.

Operational

Many pilots who flew the Westland Whirlwind held it in high regard for its performance. Sergeant G. L. Buckwell of 263 Squadron, who was downed over Cherbourg in a Whirlwind, reflected on its qualities by stating, “It was great to fly – we were a privileged few… In retrospect, the lesson of the Whirlwind is clear… A radical aircraft needs either prolonged development or extensive service to realize its potential and iron out flaws. During World War II, such aircraft often underwent rushed development or saw limited service, leading to initial teething problems being viewed as permanent flaws.”

Another pilot from 263 Squadron expressed, “It was regarded with absolute confidence and affection.” However, test pilot Eric Brown had a less favorable view, describing the aircraft as “under-powered” and “a great disappointment.”

Whirlibomber of No. 137 Squadron RAF, Manston 1943

Whirlibomber of No. 137 Squadron RAF, Manston 1943

One frequent critique of the Whirlwind was its high landing speed, necessitated by its wing design. Due to the limited number of Peregrine engines produced, no redesign of the wings was planned, though Westland experimented with leading-edge slats to lower landing speeds.

Unfortunately, these slats were deployed with such force that they tore off, leading to them being permanently wired shut.

German E-boats in the English Channel

At higher altitudes, the performance of the Peregrine engines diminished, likely affected by the propeller profile and the constant speed prop controller. Consequently, the Westland Whirlwind was primarily employed in ground-attack missions over France, targeting German airfields, marshalling yards, and railway traffic.

It excelled as a gun platform, particularly in destroying locomotives, with some pilots credited with damaging or destroying multiple trains in a single mission. The aircraft also proved effective against German E-boats in the English Channel.

At lower altitudes, it was capable of competing with the Messerschmitt Bf 109. Despite criticisms of the Peregrine, it was more reliable than the troubled Napier Sabre engine used in the Hawker Typhoon, the Whirlwind’s successor.

The twin-engine design of the Whirlwind allowed damaged aircraft to return with one engine disabled. The forward placement of the wings and engines provided significant damage absorption, protecting the cockpit area. This robust construction offered pilots enhanced safety during crash landings and ground accidents compared to other contemporary aircraft.

Night Fighters

The initial deployment of the Whirlwinds was to 25 Squadron, stationed at North Weald, which was already fully outfitted with radar-equipped Bristol Blenheim IF night fighters. On May 30, 1940, Squadron Leader K. A. K. MacEwen piloted the Whirlwind prototype L6845 from RAF Boscombe Down to RAF North Weald.

The aircraft was flown and evaluated by four pilots from the squadron the following day, and inspected by the Secretary of State for Air, Sir Archibald Sinclair, and Lord Trenchard the day after. In June, the first two production Whirlwinds were delivered to 25 Squadron for night-flying trials.

However, it was soon decided to switch the squadron to the two-seat Bristol Beaufighter night fighter, leveraging its existing status as an operational night fighter squadron.

Whirlwinds squadron in flight

Whirlwinds squadron in flight

The first squadron to be fully equipped with Whirlwinds would be 263 Squadron, which was reassembling at RAF Grangemouth after suffering severe losses in the Norwegian Campaign.

The squadron’s commander, Squadron Leader H. Eeles, delivered the first production Westland Whirlwind on July 6. Delivery pace was sluggish, with only five aircraft with 263 Squadron by August 17, 1940, and none of them were serviceable.

The squadron temporarily augmented its fleet with Hawker Hurricanes to maintain pilot flight readiness during this period. Despite the ongoing Battle of Britain and the critical need for fighters, 263 Squadron stayed in Scotland.

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, head of RAF Fighter Command, stated on October 17 that 263 could not be moved to the south as there was no room for “passengers” in such a strategically crucial area.

Westland Whirlwind Was Lost

The first Whirlwind was lost on August 7 when Pilot Officer McDermott experienced a tire blowout during takeoff in aircraft P6966. Remarkably, he managed to get the aircraft airborne. However, after being informed by Flying Control about the compromised condition of his undercarriage, PO McDermott bailed out between Grangemouth and Stirling.

The aircraft subsequently dived into the ground, burying itself eight feet deep. A later inspection of the salvaged wreckage revealed that the tire fitted was not the correct size for the Westland Whirlwind but rather for a Hurricane, which 263 Squadron was also operating at the time.

Chief test pilot of Westland, Harald Penrose flying one of the last production Whirlwinds P7110.

Chief test pilot of Westland, Harald Penrose flying one of the last production Whirlwinds P7110.

263 Squadron subsequently relocated to RAF Exeter and was declared operational with the Whirlwind on December 7, 1940. Initial missions involved convoy patrols and anti-E-boat operations. The squadron’s first confirmed enemy engagement occurred on February 8, 1941, when a Westland Whirlwind shot down an Arado Ar 196 floatplane.

Tragically, the Whirlwind also crashed into the sea, and the pilot was killed. From that point, the squadron achieved notable success with the Whirlwind, engaging enemy Junkers Ju 88, Dornier Do 217, Messerschmitt Bf 109s, and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s.

Escort for 54 Blenheims

263 Squadron also undertook day bomber escort missions. For instance, they participated as part of an escort for 54 Blenheims targeting power stations near Cologne on August 12, 1941.

Due to the limited range of the Whirlwinds, the fighters turned back near Antwerp, leaving the bombers to continue without escort; ten Blenheims were lost during the raid.

The squadron predominantly carried out low-level attack sorties over the channel, known as “Rhubarbs” against ground targets and “Roadstead” attacks against shipping. On August 6, 1941, four Whirlwinds engaged a large formation of Messerschmitt Bf 109s during an anti-shipping strike and successfully claimed three Bf 109s destroyed without any losses.

Westland Whirlwind I undergoing fighter-bomber trials at the A&AEE.

Westland Whirlwind I undergoing fighter-bomber trials at the A&AEE.

A second Whirlwind squadron, No. 137, was established in September 1941, focusing on attacks against railway targets. By the summer of 1942, both squadrons had been equipped with racks for carrying two 250 or 500 lb bombs, earning the nickname ‘Whirlibombers.’ These aircraft performed low-level cross-channel “Rhubarb” sweeps, targeting locomotives, bridges, shipping, and other infrastructure.

Whirlibombers

In late 1942, the Whirlwind was modified to serve as a bomber, joining the ranks of the Hurribomber in carrying out attacks against enemy forces in occupied territories with both cannons and bombs, by day and night. Each aircraft was equipped to carry one 250 or 500 lb bomb under each wing, earning the informal nickname “Whirlibombers.”

The initiative to fit bomb racks on the Whirlwinds was pushed by Squadron Leader T. Pugh, D.F.C., the commanding officer of No. 263 Squadron, as early as September 1941. However, it wasn’t until July 21, 1942, that the first Whirlwind of the squadron was modified to carry bombs.

Bombing up a Whirlwind of No. 137 Squadron RAF, Manston 1943

Bombing up a Whirlwind of No. 137 Squadron RAF, Manston 1943

The inaugural mission of the “Whirlibomber” by No. 263 Squadron, intended merely as a trial, took place on September 9, 1942. Two sections, escorted by Spitfires, targeted four armed trawlers moving from Cap de la Hague near Cherbourg towards Alderney.

The mission was a resounding success with two of the trawlers sunk. These operations were conducted without a bomb sight, and given the Whirlwinds typically bombed from heights of 50 feet or less, a delayed action fuse was selected.

When loaded with bombs, the aircraft had a tendency to fly with the left wing lower during dives, and pilots experienced aileron snatch at high speeds.

Westland Whirlwind Brest and Cherbourg Peninsulas

It was recommended that both bombs be released simultaneously during low-level attacks, although pilots could opt for two bombing runs, dropping the port-side bomb first.

The two Whirlwind squadrons relentlessly attacked the enemy with bombs and cannon until the Typhoon took over in 1943. No. 263 Squadron primarily operated over the Brest and Cherbourg Peninsulas and the Western Approaches, while No. 137 Squadron covered the Channel and Northern France from their base at Manston. Railway lines were especially visible in moonlight, with smoke signals indicating an approaching train.

When targeting railways, the Whirlwind’s four 20 mm Hispano cannons were highly effective. Indeed, one pilot from No. 137 Squadron destroyed four locomotives in a single mission. In their first six months of fighter-bomber operations, No. 137 Squadron hit thirty-seven goods trains, sixteen at night and the rest during daylight.

Daylight missions focused on goods trains, but at night, passenger trains were also targeted, as travel restrictions meant only Germans moved by train during these hours. Enemy airfields were also frequent targets, subjected to low-level attacks by the aggressive “Whirlibomber” pilots.

Westland Whirlwind Ambushed

137 Squadron suffered its heaviest losses on February 12, 1942, during a mission to escort five British destroyers. Unbeknownst to them, the German warships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were executing the Channel Dash to reach safer ports.

Scharnhorst pictured in 1939. Image by Bundesarchiv CC BY-SA 3.0

Scharnhorst pictured in 1939. Image by Bundesarchiv CC BY-SA 3.0

Four Whirlwinds launched at 13:10 hours and soon spotted warships approximately 20 miles (32 km) off the Belgian coast through the clouds.

As they descended to investigate, about 20 Bf 109 fighters from Jagdgeschwader 2 ambushed them. Despite being vastly outnumbered and engaging any target they could, four of the eight Whirlwinds dispatched that day did not return; two additional Whirlwinds had joined at 13:40 and another pair at 14:25 to provide relief.

From October 24 to November 26, 1943, 263 Squadron carried out several intense attacks on the German blockade runner Münsterland, then in dry dock at Cherbourg. Up to 12 Whirlwinds at a time conducted dive-bombing runs from altitudes between 12,000 and 5,000 feet (3,700 and 1,500 meters), dropping 250 lb (110 kg) bombs.

Westland Whirlwind “Rhubarb” Attack

Despite heavy anti-aircraft fire, nearly all bombs landed within 500 yards (460 meters) of the target, with only one Whirlwind lost during these operations.

The final mission flown by Whirlwinds of 137 Squadron occurred on June 21, 1943, targeting the German airfield at Poix in a “Rhubarb” attack. One aircraft, unable to locate the target, bombed a supply train north of Rue instead.

On its return, the starboard throttle stuck open, eventually leading to engine failure and a forced landing next to RAF Manston. The aircraft was destroyed, but the pilot, as often happened with the robust Whirlwind, emerged unscathed.

263 Squadron, the first and last to operate the Whirlwind, flew its final mission with the type on November 29, 1943. In December, the squadron transitioned to the Hawker Typhoon. By January 1, 1944, the Whirlwind was officially declared obsolete.

Remaining serviceable aircraft were moved to No. 18 Maintenance Unit, and those in the process of repairs were only to be completed if nearly flyable. An official directive prohibited further repair work on aircraft needing extensive maintenance.

News

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering Perched precariously on the cliffs of Mount Heng in Shanxi Province, China, the Hanging Temple, also known as Xuankong Temple, Hengshan Hanging Temple, or Hanging Monastery, is an architectural…

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets The “Willendorf Venus” stands as one of the most revered archaeological treasures from the Upper Paleolithic era. Discovered in 1908 by scientist Johann Veran near Willendorf, Austria, this small yet profound…

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts New archaeological research has uncovered intriguing insights into the ritual practices of the ancient Maya civilization. The focus of this study is a ceremonial offering found beneath the sediment…

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins The history of agricultural innovation is a fascinating journey that spans thousands of years, and one of the earliest known agricultural machines is the threshing sledge. Recently, a groundbreaking study…

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits In a remarkable discovery that has captured the attention of archaeologists and historians alike, a 7.5-foot-long iron sword was unearthed from a 1,600-year-old burial mound in Nara, Japan. This oversized weapon,…

The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots

Experimental The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots The Inflatoplane from Goodyear was an unconventional aircraft developed by the Goodyear Aircraft Company, a branch of the renowned Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, also famed for the Goodyear…

End of content

No more pages to load