The “Lady of Cavigflione” is a woman who lived approx 24 000 years ago. Mothers of Time – Ventimiglia (IM)

Mothers of Time – Ventimiglia (IM)

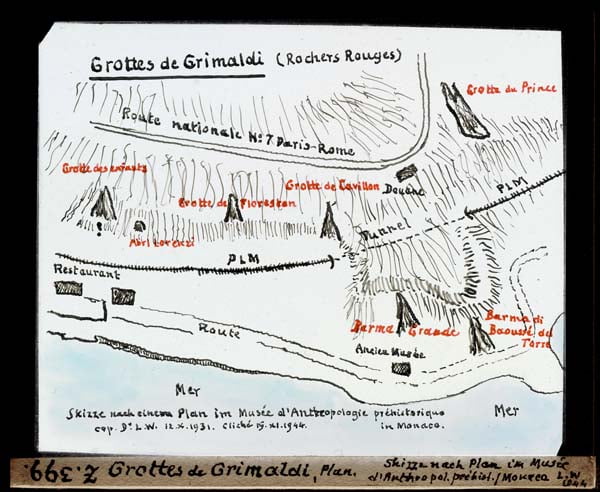

1944 plan sketch of the Grimaldi Caves, kept in the ETH Zurich Library

di Elvira Visciola

The complex of Balzi Rossi or Grimaldi, so called from the nearby village, has been the subject of numerous archaeological investigations since the mid-800s which have brought to light paleontological and archaeological finds and testimonies belonging to the various phases of the Paleolithic. The complex is located at the border crossing with France (Valico di Ponte San Ludovico), made up of cliffs of calcareous rocks mixed with red ferrous materials, at the base of which there are shelters and more or less large cave cavities (the “Bausi”, i.e. holes, thus transformed into “Balzi Rossi”), long inhabited by prehistoric populations: there are remains of human occupation and burials from the Lower Paleolithic (from 350.000 to 300.000 years ago) to the Upper Paleolithic (from 35.000 to 10.000 years ago), including the Middle Paleolithic, thus attesting the presence of the Neanderthal Man, the Cro-Magnon, and a specific human type called Grimaldi Man. The discoveries that have taken place on site, twelve burials of which two doubles and one triple with the associated funerary objects, fifteen female statuettes (Venuses) attributable to the Paleolithic, expressions of wall art, abundant remains of lithic industry and fauna have meant that the Balzi Rossi complex has leapt to the news as one of the most important Paleolithic sites in Europe. The complex consists of the following caves and shelters: Grotta dei Fanciulli, Riparo Lorenzi, Grotta di Florestano, Grotta del Caviglione, Barma Grande, Baousso da Torre and Grotta del Principe.

Archaeological investigations began in 1846, when Prince Florestano of Monaco began an intense excavation activity in the cave that bears his name, sending some finds to Paris, materials which will then be dispersed; at that time the official recognition of the Palaeolithic had not yet taken place, therefore it was not possible to evaluate exactly the scope of the finds. It was only in 1870 that, with the works on the railway between Genoa and Marseilles and with the transfer to the area of Emile Rivière (French doctor), the first productive excavations began.

To let the tracks pass, a deep trench was dug in the area in front of the caves with the discovery of numerous finds, most of which were purchased by Rivière who, with the enthusiasm of the moment, moved to obtain from the French authorities in 1871 financing and the excavation permit at the Balzi Rossi, a very curious event as the Caves, following the Treaty of Turin of 1860, i.e. after the 2nd War of Independence, were openly Italian property. The first complaints from the Italian authorities soon arrived until Rivière obtained the Italian excavation permits. Not satisfied, he bought the Barma Grande, the Baousso da Torre and the Grotta del Principe, while as local inhabitants he acquired the exclusive rights to exploit the Grotta dei Fanciulli, the Riparo Lorenzi, the Grotta di Florestano and the Grotta del Caviglione; from that moment he began to dig in the various caves until 1875.

In March 1872, together with Stanislas Bonfils (local archeology enthusiast) he brought to light the first burial in the Caviglione cave at an altitude of over 6 meters of excavation, initially attributed to an adult Paleolithic man, (called “Man of Menton” ) and only later, following further in-depth studies up to 2016, rightly attributed to a woman of the Gravettian era, called the “lady of Caviglione”, dated to about 24.000 years ago, of tall stature (about 1.90 meters, typical of European Upper Paleolithic), died at the age of about 37 years. The skull was covered by a headdress decorated with sea shells, deer teeth and a large bone pin was inserted above the forehead, while other shells were found near the tibia, probably because they were part of a decorative bracelet placed on the legs. Abundant traces of red ocher have been found both on the bones and on the ground and the funerary equipment with horse bones, typical elements of Paleolithic burials. The skeleton was leaning on the left side in a fetal position, with the hands close to the face, two flint arrowheads and a large bone pierced at one end placed on the chest, as if it were part of a necklace; the skeleton presented a fracture near the wrist and attested the gestation of at least one child. The find was transferred to Paris, to the Institut de Paléontologie Humaine and exhibited at the Musée de l’Homme, together with the portion of land on which the body lay with traces of charred stones; the cast of the same is kept in the Balzi Rossi Museum. The burial of the Lady of Menton, found by Emile Rivière on 26 March 1872 in the Grotta del Caviglione. The illustration was taken from a photograph taken at the time of discovery (ph. V. Formicola et al., 2015)

The burial of the Lady of Menton, found by Emile Rivière on 26 March 1872 in the Grotta del Caviglione. The illustration was taken from a photograph taken at the time of discovery (ph. V. Formicola et al., 2015)

In 1873 he found three burials in the Baousso da Torre, a teenager lying in an unusual position, face down, and two adults with the relative grave goods, at a depth of about 3.70-3.90 m. from the original soil of the cave; two of these burials, previously considered lost, are in the Musée Lorrain in Nancy and the other is in the National Museum of Antiquities in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, near Paris. The physical characteristics and the funerary equipment were similar to those of the Grotta del Caviglione.

In 1874 another important discovery took place, two infant burials in the Grotta dei Fanciulli, which took its name from the discovery, at an excavation depth of 2.70 m; the two children were placed next to each other, in a supine position, with numerous pierced shells arranged around the hip, as if they were part of the ornament of a dress; examinations carried out on the teeth made it possible to assign the children an age of 2 and 3 years. Rivière sent everything to Paris where they are currently exhibited at the Musée des Antiquites Nationales in Saint Germain-en-Laye. The two infant burials in the Grotta dei Fanciulli

The two infant burials in the Grotta dei Fanciulli

Around 1880 Francesco Abbo, a small local businessman, became the owner of the Barma Grande and the Baousso da Torre, parading them at the Rivière; he had no interest in archeology but rather thought of using the filling of the Barma Grande as fertilizer for the soil of one of his vineyards. The news reached Prince Albert of Monaco, who, particularly interested in prehistory, contacted Abbo to agree on preventive excavations which he began to do in 1882 with more scientific methods, through rigorous documentation of the stratigraphy; disputes with the owner, however, forced him to temporarily abandon the search.

But it was only with the appearance of Louis-Alexandre Jullien, a merchant from Marseilles, that the most interesting discoveries of the Barma Grande arrived; with the collaboration of Bonfils, in December 1883 the first two statuettes of the Balzi Rossi came to light, currently known as the “lady with goiter”And the”yellow soapstone figurine” (discovered on 18 and 23 December 1883 respectively). At that moment the two finds aroused a certain embarrassment, the female statuettes of the Paleolithic were not yet known and the nudity they represented was disconcerting for the time; Jullien thus decided to hide the find, also because the smooth features of the statuettes referred to the Neolithic and therefore, fearing that his discoveries were considered coeval, he tried to disguise everything. In February 1884 a new burial came to light, the skeleton of an adult man in good condition, sprinkled with red ocher and with a funeral kit of flint blades, but following a scuffle with Mr. Abbo, the skeleton was destroyed and Jullien’s excavation license revoked. Some remains of the skeleton, skull and part of the femur were exhibited at the Mentone Museum, while other fragments and the funerary equipment were transferred by Jullien to the Peabody Museum of Harvard University in Cambridge in the USA. Abbo posing in the Barma Grande, in a 1910 photo by Henri-Marc Ami (ph. M.Mussi et al., 2008)

Abbo posing in the Barma Grande, in a 1910 photo by Henri-Marc Ami (ph. M.Mussi et al., 2008)

The subsequent discoveries in the Barma Grande, which occurred at a depth of about 11 meters from the original level, date back to February 1892 with the triple burial, three skeletons dating back to about 20.000 years ago, an adult male 1.90 tall with powerful skeletal strength and two girls, probably sisters placed with their father or other close relative, neatly placed side by side in the same grave, sprinkled with red ocher with a rich array of sea shells, deer teeth, worked bone pendants and flint blades; in the academic field the find is considered of particular importance, as it is one of the rare examples of triple Paleolithic burial, in the world there is only one other example in the Czech Republic. The triple burial of the Barma Grande with the rich funeral equipment

The triple burial of the Barma Grande with the rich funeral equipment

In 1894 a new discovery in the internal part of the Barma Grande caused a sensation: they were 2 burials of adult males, placed a short distance from each other, at a depth of about 6.40 m. The peculiarity was that one of the two skeletons rested on an ancient hearth, which initially made one think of a case of combustion of the corpse, but later it was ascertained that it had been placed on an extinguished hearth.

In the meantime, Prince Albert of Monaco, fascinated by the history of the caves, bought the cave that currently bears his name as an exclusive property, considered at the time still intact from the excavation activities carried out up to then and from 1895 to 1902 promoted an intense activity with an interdisciplinary team, entrusted to canon L. De Villeneuve and M. Boule. The caves affected by the works were first the Grotta del Principe and then the Grotta dei Fanciulli, while the excavations at Riparo Lorenzi and the Grotta del Caviglione were of little interest. The Grotta dei Fanciulli yielded several burials; in the upper layers, contiguous to those from which the two children came, the burial of an adult woman came to light in a poor state of conservation, buried in a supine position. From the lower levels instead emerged the burial of an adult male individual, of tall stature and vigorous structure, placed with his hands on his chest, but the most important find was the so-called double burial known as the “Negroid”, containing an old woman with a seashell bracelet and a teenager of about 15-17 years old with a headdress made of four rows of seashells. The two bodies were in a crouched position with the head protected by a series of stones arranged in a box; they had different characteristics compared to the other burials found in the Balzi Rossi, for example a smaller stature (1.59 the woman and 1.56 the boy) and a different morphology of the skull (more similar to the negroid races), so much so that there was talk of a new human type called Grimaldi breed. However, studies of the sixties demonstrated the groundlessness of this hypothesis, the two bodies had been buried at different times, attributable to the Gravettian. The observations on the burials of this period and the presence of the funerary objects, of the red ocher and of the ornaments finally demonstrated the existence of real funeral rites in the Upper Paleolithic. The double burial known as the Negroids in the Grotta dei Fanciulli (ph. V. Formicola et al., 2015)

The double burial known as the Negroids in the Grotta dei Fanciulli (ph. V. Formicola et al., 2015)

All the finds recovered by Prince Albert were exhibited in the Musée d’Anthropologie Préhistorique that he himself had set up in 1902 in the Principality of Monaco, while the English patron Thomas Hanbury had provided for the construction of the Museum Praehistoricum in the Balzi Rossi archaeological area in 1898 , in order to welcome and exhibit, at least in part, the exceptional finds from the profitable excavation activities. The Museum Praehistoricum in a 1910 photo by Henri-Marc Ami (ph. M. Mussi et al., 2008)

The Museum Praehistoricum in a 1910 photo by Henri-Marc Ami (ph. M. Mussi et al., 2008)

From the Grotta del Principe emerged the fragment of the pelvis of a woman of the Heidelbergensis type, therefore dating back to about 250.000 years ago in the Lower Paleolithic, currently exhibited in the Balzi Rossi museum. During these excavations begun in 1895, the Prince actually ascertained that the cave was not intact, but had already been excavated clandestinely by Jullien in the years between 1892 and 1895, as he later managed to discover; on this occasion he had brought to light another thirteen figurines of the Upper Paleolithic which he took with him to Canada by stealing them. Meanwhile, in 1892 Edouard Piette, a magistrate collector of prehistoric art, discovered the so-called Venus in Brassempouy, a statuette dated to the Upper Paleolithic, arousing disbelief in the scientific community, so much so that in 1894, again in Brassempouy, a sort of hunt was organized treasure with the discovery of two other ivory statuettes, now known as l’Ebauche and la Poire and the consequent attribution of these finds to ancient prehistory. Thanks to this discovery, the existence of these statuettes dated to the Gravettian was finally recognized.

At this point Jullien from Montreal made known the existence of the fifteen figurines recovered at the Barma Grande and in the Grotta del Principe, in an attempt to find a buyer. He proposed for sale the so-called “Yellow Venus” (no. 04) to Salomon Reinach, then director of the Museé des Antiquités Nationales in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, together with other objects from the Barma Grande, objects which immediately became part of the museum’s collection. Edouard Piette, having become aware of the existence of the finds, bought from Jullien on two different occasions, since 1896, you are figurines, the Lozenge, the Pulcinella, the Hermaphrodite, the Lady with the goiter, the Negroid Head and the last in 1902, the Innominata; all of them will later merge into the Saint-Germain-en-Laye Museum where they are currently exhibited. But, curious detail, despite the importance of the acquisition, Piette did not exhibit the precious material: only in 1902 did he publish one of his articles in which he spoke of “smaller and less well-sculpted” statuettes than those of Brassempouy, publishing the photos only of the Negroid Head and Pulcinella and making racist observations that fit well into the colonial prejudices of the time.

Even the Abbot Henry Breuil took an interest in the statuettes, commissioning one of his brothers, the Abbot Dupaigne who lived in Montreal, to find information about them; in 1915 he obtained from him a schematic drawing of two of the statuettes, those called the Bust and the Janus, information published by him only in 1930. For the statuettes it will be necessary to wait more than half a century to see them return to the limelight, it seems that Jullien tried to sell them but the events of the First World War put an end to any negotiation. After her death in 1928, one of her daughters who in the meantime had moved to the United States, Laurence, in 1944 gave the Peabody Museum of Harvard University the “figurine with pierced neck” or “Giano” and about 380 stone tools found by Jullien in the excavations at Barma Grande. Five more only re-emerged from oblivion in 1987 when Jullien’s granddaughters sold a trunk containing the statuettes to a Montreal antique dealer, which, in November of the same year, were purchased by a Montreal sculptor, Pierre Bolduc, for $225. After a few years, in 1993 Bolduc took them to McGill University in Montreal for evaluation and analysis with confirmation that the 5 figurines were indeed the missing part of the long lost Jullien collection. At Bolduc’s insistence, Jullien’s nieces, Lucie and Laurence Jullien-Lavigne, found the last two figurines, the Bust and the Two-headed.

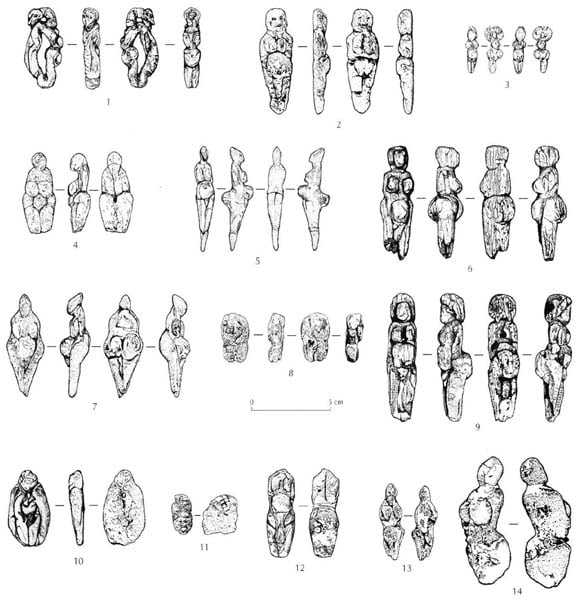

After a true “damnatio memoriae” at the beginning of the century due first to Jullien’s concealment of the statuettes after their discovery and subsequently to the questioning of their authenticity, both for the dating and for the suspicion that Jullien was a fraud, the 15 figurines had finally come to light again. The seven Canadian figurines they were exhibited to the public only once, in 1995 at the Canadian Museum of Civilization in Hull, Quebec, for the exhibition entitled “Mothers of Time”, curated by the archaeologist Jacques Cinq-Mars, with the collaboration of the Italian archaeologist Margherita Mussi . The 14 figurines of the Balzi Rossi (drawings White and Bisson, 1998)

The 14 figurines of the Balzi Rossi (drawings White and Bisson, 1998)

Returning to the activity of excavating caves, the Italian Institute of Human Paleontology was established in Florence in 1927, which from 1928 to 1930 excavated both in the Barma Grande and in the Mousterian levels of the Grotta dei Fanciulli, to then continue after 1938 with excavations at the Riparo Bombrini and Mochi, both important for the stratigraphic sequence from the Middle Paleolithic to the Epipaleolithic, which made it possible to investigate a crucial moment in the evolutionary history of man, in the transition phase from Neanderthal man to Upper Paleolithic man. In fact, up until then all on-site research had been entrusted to pioneers who had often used excavation techniques that were not always appropriate with the consequent loss of important information; it should be noted that these modalities were not exceptional for the time, just think that the first regulation on archaeological excavations in Italy took place in 1939, even if partial provisions had been issued previously (1909 and 1919).

During the Second World War, the bombing of the railway seriously damaged both the Balzi Rossi archaeological area and the nearby museum, rebuilt and enlarged in 1953-54. At the time, the finds were saved thanks to the timely intervention of Luigi Cardini, a renowned paleontologist.

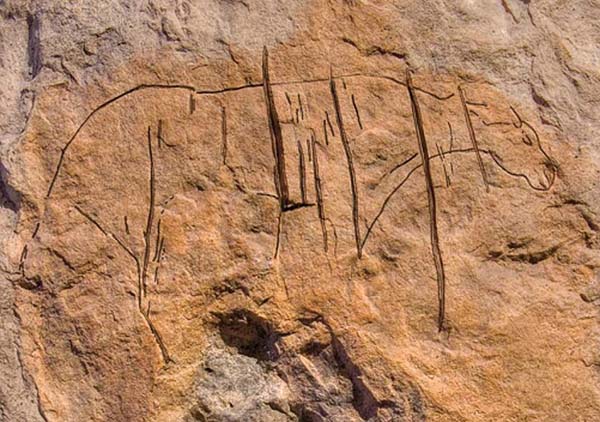

In 1971, near the Mochi shelter, the first traces of Palaeolithic wall incisions were noticed, which raised the doubt that probably also in the other caves there were graffiti at the original level, before the excavation; thus all the caves at their respective altitudes were examined with the discovery of the most important representation, that relating to a small horse from the Caviglione Cave, about 7 meters above the current level, a figure crossed by various vertical segments. This incision, about 40 cm. in length, it resembles the current types of animals of the Camargue or the wild type of Eastern Europe; in-depth studies ascertained that two of the linear signs were made before the graffiti of the horse, information of considerable importance since it would seem to prove that the linear signs were widespread throughout the Paleolithic while the horse would belong to the purely Gravettian cultures, therefore coeval with the statuettes. Other engravings are present in the Blanc-Cardini shelter. The horse found in the Grotta del Caviglione

The horse found in the Grotta del Caviglione

In recent times the excavation activity has continued in the Riparo Mochi, in the Grotta del Principe and in the Riparo Bombrini, searches carried out by Italian and American institutions, making sure that the Balzi Rossi complex, despite the vicissitudes described, has provided one of the most important evidence on the biology, culture and behavior of the first modern populations of Europe.

News

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering Perched precariously on the cliffs of Mount Heng in Shanxi Province, China, the Hanging Temple, also known as Xuankong Temple, Hengshan Hanging Temple, or Hanging Monastery, is an architectural…

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets The “Willendorf Venus” stands as one of the most revered archaeological treasures from the Upper Paleolithic era. Discovered in 1908 by scientist Johann Veran near Willendorf, Austria, this small yet profound…

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts New archaeological research has uncovered intriguing insights into the ritual practices of the ancient Maya civilization. The focus of this study is a ceremonial offering found beneath the sediment…

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins The history of agricultural innovation is a fascinating journey that spans thousands of years, and one of the earliest known agricultural machines is the threshing sledge. Recently, a groundbreaking study…

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits In a remarkable discovery that has captured the attention of archaeologists and historians alike, a 7.5-foot-long iron sword was unearthed from a 1,600-year-old burial mound in Nara, Japan. This oversized weapon,…

The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots

Experimental The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots The Inflatoplane from Goodyear was an unconventional aircraft developed by the Goodyear Aircraft Company, a branch of the renowned Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, also famed for the Goodyear…

End of content

No more pages to load