Northrop YB-35/XB-35 – The Flying Wing Failure

In 1938 after setting up his independent venture, engineering legend John Northrop could finally work on a project he had been putting off for almost 10 years.

Northrop had been obsessed with making a clean wing design that didn’t feature struts or bracing wire, in the belief that such a configuration had superior aerodynamic characteristics.

Emerging from the other side of the Great Depression, in which the great aviation maverick had survived by solely building production aircraft, Northrop now had enough financial wiggle room to experiment again with the flying wing, which he would call the Northrop XB-35.

N1-M

In 1938 Northrop kicked off proceedings by drawing a rough sketch of a pure flying wing without a drag-producing tail, making sure also to draw drooped wingtips for directional stability as well as a couple of newfangled components called ‘elevons’, which combined the functions of the elevator and the aileron.

Before the N1-M Northrop had experimented with other flying wing designs.

Before the N1-M Northrop had experimented with other flying wing designs.

Next with the assistance of Dr Theodore von Karman, Director of the Guggenheim School of Aeronautics, and his assistant William Sears, a scale model called the N1-M, an all-yellow craft nicknamed ‘Jeep,’ was assembled.

The N1-M took to the skies for the first time in July 1940 with seasoned aviator Vance Breese at the controls and quickly became an invaluable source of data. With its welded steel tube and wooden construction making it easy to reconfigure the structure, Northrop was able to change the dimensions when required and to test them just as fast.

200 Spins

Soon Breese and Moye W. Stephens, who would take the N1-M for over 200 spins, were singing the flying wing’s praises and noting how the exclusion of fins, empennage, and fuselage sections was causing the flying wing to accelerate at an incredibly fast rate.

The only N1-M – this aircraft first took flight in 1940. Photo credit – Alan Wilson CC BY-SA 2.0.

The only N1-M – this aircraft first took flight in 1940. Photo credit – Alan Wilson CC BY-SA 2.0.By the end of 1941, as N1-M assessments were wrapping up, the US Army expressed an interest in the new design, with General Henry H Arnold asking Northrop if it could be repurposed as a long-range heavy bomber that could be used for the intercontinental bombardment of Nazi Germany.

Anticipating the extortionate cost the of the project, Northrop was delighted to have the Army, and their inexhaustible funds, on his side. As a result, Airplane Specification NS-9A was issued in January 1942 calling for the creation of two XB-35 prototypes.

N-9M-1 and N-9M-2

Increasing the wing area from 27.8 meters squared to 45.5 meters squared, a much larger one-third model of the N1-M was next built to more accurately determine the characteristics of the flying wing.

This second iteration, the N-9M-1, first flown on December 27th 1942 and powered by two 193 kilowatt Menasco-C6S-4 engines, was also expected to have an endurance of 32 hours and an altitude ceiling of 21,500 feet.

It was made out of a mixture of wood and steel and featured an unusually small cockpit that had been crammed full of equipment and had a non-adjustable seat and rudder pedals.

The N-9M was a scaled-up version of the N-1M. Photo credit – Tim Felce CC BY-SA 2.0.

The N-9M was a scaled-up version of the N-1M. Photo credit – Tim Felce CC BY-SA 2.0.

However, after only 22.5 hours of flight time and hardly any research data accumulated, the N-9M-1 crashed on May 19th 1943 and killed test pilot Max Constant, who had been unable to deal with overpowering aerodynamic forces on his aft side, which had trapped him in his cockpit and made it impossible to reach the controls.

With a bubble canopy installed for better visibility and a one-shot hydraulic boost device put in place to push the controls forward in an emergency, the N-9M-2 would prove to be a lot more endurable than its predecessor after the completion of its maiden voyage on June 24th 1943.

During the first spate of test runs that ended in April 1944, engineers learnt that the drag of the projected XB-35 at cruising speed would actually be 7% to 12% greater than that estimated from wind tunnel tests.

A complication of shots of the N-9M at the Chino Airshow.

A complication of shots of the N-9M at the Chino Airshow.

The results were nevertheless still quite encouraging, and by June 1944 confidence was so high that the N-9M-2 was being flown as a trainer vehicle by USAF pilots.

In October 1944 evaluations were finally completed after a total flight time of 50 hours while another variant, the two-passenger N-9MB, was being finished off. On the other hand, the overwhelming demand for the P-61 Black Widow would mean the development cycle for the XB-35 would now be delayed until after the Second World War.

The Flying Wing

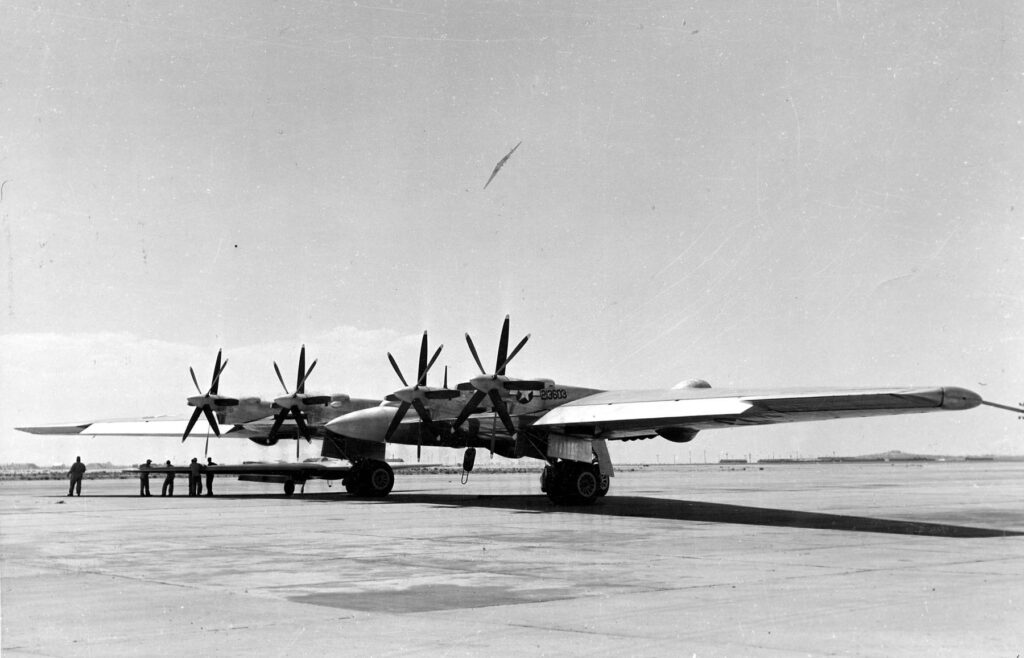

The XB-35 was an all-wing craft that accommodated a crew of 9 and was 16.3 meters long, 6.29 meters high, had an empty weight of 43,245 kilograms, and a maximum weight of 102,170 kilograms.

Its enormous aerodynamically efficient wing had a span of 52.5 meters and an area of 371 meters squared and was controlled using a complex system of elevons, trim flaps, and rudders. The XB-35 originally had Hamilton-Standard contra-rotating propellers that were powered via four Pratt & Whitney Wasp Major engines equipped with single-stage general Electric turbosuperchargers.

It was later revamped with single-rotation propellors, while its piston engines were replaced with General Electric TG-180 turbojets which gave it a top speed of 391 miles per hour, a combat radius of 8,150 miles, and a service ceiling of 39,700 feet.

The XB-35 was massive.

The XB-35 was massive.

The XB-35 was to be decked out with an arsenal that included a 4,500-kilogram bomb load and seven powered turrets employing 20 mm cannons. Interestingly, no defensive armament was implemented because it was anticipated the flying wing would use its agility to evade interceptors.

On May 16th 1946, the No.1 XB-35 was rolled out at Muroc Dry Lake for routine taxi tests in which it achieved speeds of 115 miles per hour.

Less Fanfare

The first flight occurred on June 25th 1946 rather inconspicuously because of a company-wide order that had, to control the crowd, restricted the number of bystanders allowed to watch it, a directive that even company director John Northrop had obeyed by staying at his desk. On June 26th 1947 the No.2 XB-35 also arrived, but to considerably less fanfare.

The XB-35 under construction.

The XB-35 under construction.

The XB-35 would be one of the first craft evaluated with the help of television cameras, which pointed at flight instrumentation panels, and broadcasted pictures live to a P-61 chase plane.

Besides a couple of issues with the propellors, the initial assessments were promising, encouraging the Air Force to make an order for six production units designated YB-35, which would have greater range and would be able to carry a heavier bomb load.

On the other hand, the XB-35 program would soon be threatened by widespread rumours that the Convair XB-36 was the likely winner of the Air Force’s competition to find a new piston-engined strategic bomber.

To keep the project alive and still at the forefront of aviation, Northrop recommended that two of the YB-35s be completed as turbojet-powered YB-49s.

The first XB-35 with dual contra-rotating 3-blade propellers.

The first XB-35 with dual contra-rotating 3-blade propellers.

The first YB-49 was unveiled to the public on September 29th 1947 and debuted on October 21st 1947 where it experienced only minor issues. In contrast, the XB-35 was running into increasingly insurmountable obstacles. Counter-rotating propellers were once again to blame, with the malfunction centering on the gearbox and the propellor governor.

Tragedy

Surveying the situation, contractors agreed that the drive to finish the XB-35 outweighed any minor performance penalties of the existing propellor, and so a decision was made to ignore it; although not completely, for the two XB-35s were also refitted with a brand new set of four-bladed, single rotational propellors with a much larger diameter.

With the XB-35s being overhauled focus naturally re-shifted to the YB-49, whose great start to the development stage would soon be overshadowed by the spectre of tragedy.

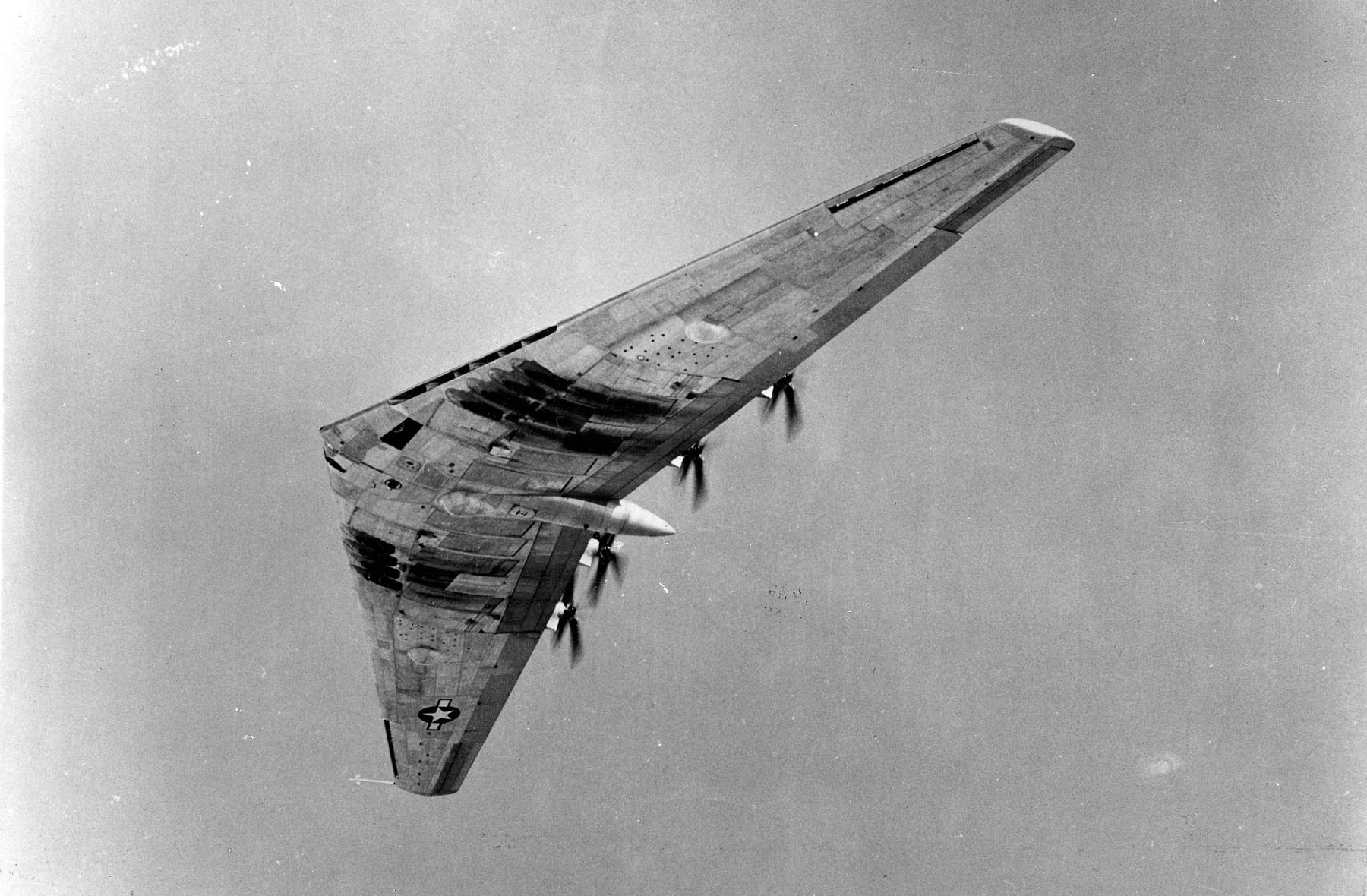

It certainly looked elegant in flight.

It certainly looked elegant in flight.

On June 5th 1948 after shedding its two outer wing sections, the No.2 YB-49 crashed over the Antelope Valley test range, killing every member of the five-man crew. Despite the incident though, the US Army’s confidence in both planes never faltered, and only five days after they would announce an order for 30 YB-49s.

Downfall

On the other hand, the US Army’s highly publicized purchase of YB-49s would be the high point for the program, which began to rapidly decline from then on out.

The first crack was the XB-35 program which began to be plagued by insuperable problems. The most exasperating issue was with the single rotation propellors, which produced recurring vibration and metal fatigue, causing the engine cooling fans to break down.

Coupled with unreliable engines, an overly intricate exhaust system, and persistent maintenance problems, the XB-35’s very capacity to function as a long-range bomber was being questioned.

Befalling a similar fate was the YB-49, found to be incredibly unstable and difficult to fly, whose funding was re-diverted into a more fruitful Convair B-36/RB-36 program that needed 300 million dollars in additional funding.

The XB-35 on takeoff.

The XB-35 on takeoff.

Despite this Northrop continued to keep in contact with USAF, who in turn continued to give them hope the pause was only temporary by accepting their proposals for modified XB-35 airframes.

Hope was further reignited following the record-breaking long-distance flight of a YB-49, which in February 1949 flew a distance of 3,630 kilometres in 4 hours and 25 minutes at a speed of 822 kilometres per hour. In these latter years, increasingly desperate for the XB-35 and YB-49 program to survive.

Northrop submitted a multitude of different variants of the flying wing to USAF which included a turboprop-engined bomber, an escort fighter, and most unusually an iteration called the EB-35B, which was to be a test bed for a cutting-edge XT-37T Turbodyne gas turbine powerplant.

On January 11th 1949 Air Material Command officially discontinued the YB-49 program, the only exception being the YRB-49A, a reconnaissance craft that would fizzle out by the summer of that year and eventually be dismantled in 1953.

The next month in February both XB-35s were ordered to be scrapped and from March 15th 1950 all YB-49s were destroyed.

Northrop YRB-49A

After the B-49 project was discontinued, the Air Force proceeded to allocate funds for transforming the tenth YB-35 (42-102376) into a prototype for an unarmed, long-distance photographic reconnaissance aircraft. This modified version was designated as the YRB-49A, and internally referred to as Model NS-41 by the company.

The aircraft was equipped with four 5000 lb.s.t. Allison J35-A-19 engines, with two mounted on each wing. Additionally, two more J35 engines were attached in pods under the leading edge of the wing. This configuration of placing two engines in nacelles facilitated increased fuel storage within the wings, a necessary adaptation for the aircraft’s extended range reconnaissance missions.

Moreover, the engine pylons served a dual purpose as vertical stabilizers, which were intended to address and mitigate yaw-axis stability issues previously experienced during the testing of the YB-49A.

The crew configuration for the aircraft comprised six members: a pilot, co-pilot, flight engineer, photo navigator, radar navigator, and photo technician. The photographic equipment essential for its reconnaissance role was situated in the tail cone bay, located just beneath the center section of the aircraft.

For the intended RB-49, the internal designation used was N-37. Meanwhile, N-38 was the designation assigned to the proposed modification of the YB-49s, which was to include equipment initially planned for the RB-49.

Northrop was granted a letter contract on June 12, 1948, for preliminary engineering work. This contract, potentially leading to a production order for 30 aircraft, was officially signed on August 12, 1948. The serial numbers assigned for these aircraft were in the range of 49-200 to 49-229.

Would Lag in Speed Compared to the B-47

The Air Force, recognizing the potential benefits of combining Northrop’s engineering expertise with Convair’s experience in mass-producing large aircraft, stipulated in the contract that only one of these aircraft would be manufactured by Northrop.

The remaining 29 were to be constructed by Convair at its government-leased facility in Fort Worth, Texas. This decision was a strategic move to leverage the strengths of both companies in the development and production of this sophisticated aircraft.

It soon became clear that the six-jet RB-49A, as proposed, would lag in speed compared to the B-47. Consequently, the Air Force Board advised the immediate discontinuation of the RB-49A project. This recommendation was formally enacted in late December of 1948, leading to the redirection of funds initially allocated for the RB-49A towards additional B-36 aircraft.

The cancellation of the RB-49A project was officially confirmed in mid-January of 1949, and Northrop was instructed to halt all related work, except for the completion and testing of a single YRB-49A, which was to serve as part of a proof-of-concept research and development initiative.

The YRB-49A embarked on its inaugural test flight on May 4, 1950, flying from Hawthorne to Edwards Air Force Base.

The testing phase of the aircraft was conducted at Edwards AFB over a period. However, during its tenth test flight on August 10, 1950, a critical incident occurred when the cockpit canopy detached mid-flight, resulting in the pilot’s oxygen mask being torn off and causing minor injuries. In a fortunate turn of events, the flight engineer was able to provide emergency oxygen to the pilot in time, enabling a safe landing of the aircraft.

Left Outdoors

The YRB-49A underwent a brief phase of testing, comprising only 13 flights, before being placed in storage towards the end of 1950. In the early months of 1952, the aircraft was transported to Northrop’s facility at Ontario International Airport in California. The purpose was to install a device intended to enhance its stability.

However, by this time, the Air Force had ceased funding for the YRB-49A project, resulting in the aircraft being left in outdoor storage for an extended period. Eventually, in November 1953, the Air Force decided to scrap the aircraft.

The designation N-40 was given to an RB-49 that was ordered for conversion into a prototype of the production B-49 bomber variant.

Various engine configurations were explored for the N-40/production B-49, including eight J47s (six embedded in the wing’s trailing edge between the fins and two mounted in individual pods under the wings), six J40s, a mix of two T37s with either 2 or 4 J40s, and six J48s (Rolls-Royce Tays manufactured under license by Pratt & Whitney). The designations N-46 and N-47 were allocated to advanced design studies for the RB-49, which featured T37 turboprops.

N-50 was the designation assigned to Northrop’s proposal for modifications to the remaining YB-49 prototype to improve its stability.

However, this never came to fruition as the aircraft, 42-102367, was destroyed during a taxiing incident. N-52 was the internal designation used by Northrop for the planned Air Force test phase involving the YRB-49A, a phase that ultimately did not materialize.

News

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering Perched precariously on the cliffs of Mount Heng in Shanxi Province, China, the Hanging Temple, also known as Xuankong Temple, Hengshan Hanging Temple, or Hanging Monastery, is an architectural…

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets The “Willendorf Venus” stands as one of the most revered archaeological treasures from the Upper Paleolithic era. Discovered in 1908 by scientist Johann Veran near Willendorf, Austria, this small yet profound…

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts New archaeological research has uncovered intriguing insights into the ritual practices of the ancient Maya civilization. The focus of this study is a ceremonial offering found beneath the sediment…

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins The history of agricultural innovation is a fascinating journey that spans thousands of years, and one of the earliest known agricultural machines is the threshing sledge. Recently, a groundbreaking study…

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits In a remarkable discovery that has captured the attention of archaeologists and historians alike, a 7.5-foot-long iron sword was unearthed from a 1,600-year-old burial mound in Nara, Japan. This oversized weapon,…

The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots

Experimental The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots The Inflatoplane from Goodyear was an unconventional aircraft developed by the Goodyear Aircraft Company, a branch of the renowned Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, also famed for the Goodyear…

End of content

No more pages to load