Northrop XP-79 – The Flying Battering Ram

The Northrop XP-79 ‘Flying Ram’ was a bizarre attempt to make an aeroplane that disabled enemy craft by colliding into them in mid-air. The product of a long line of all-wing fighters originally envisioned by the founder of Northrop, the XP-79 was doomed from the start and quite predictably ended in disaster.

The Flying Wing

From the early 1920s, John K. Northrop began to seriously consider that a ‘flying wing’ plane, built without a fuselage or a tail, could be the next great step in aeronautical innovation.

Theoretically, an aircraft of this specification would have superior lifting qualities, since its entire surface would be aerodynamically efficient. In addition, it would have a much higher performance, for the streamlined configuration would ensure it had an extremely low drag.

Distracted by his work on more conventional aircraft, Northrop put the flying wing on the back burner until 1928, when after founding his own company, the Avion Corporation in Burbank, California, he attempted to make his dream into a reality.

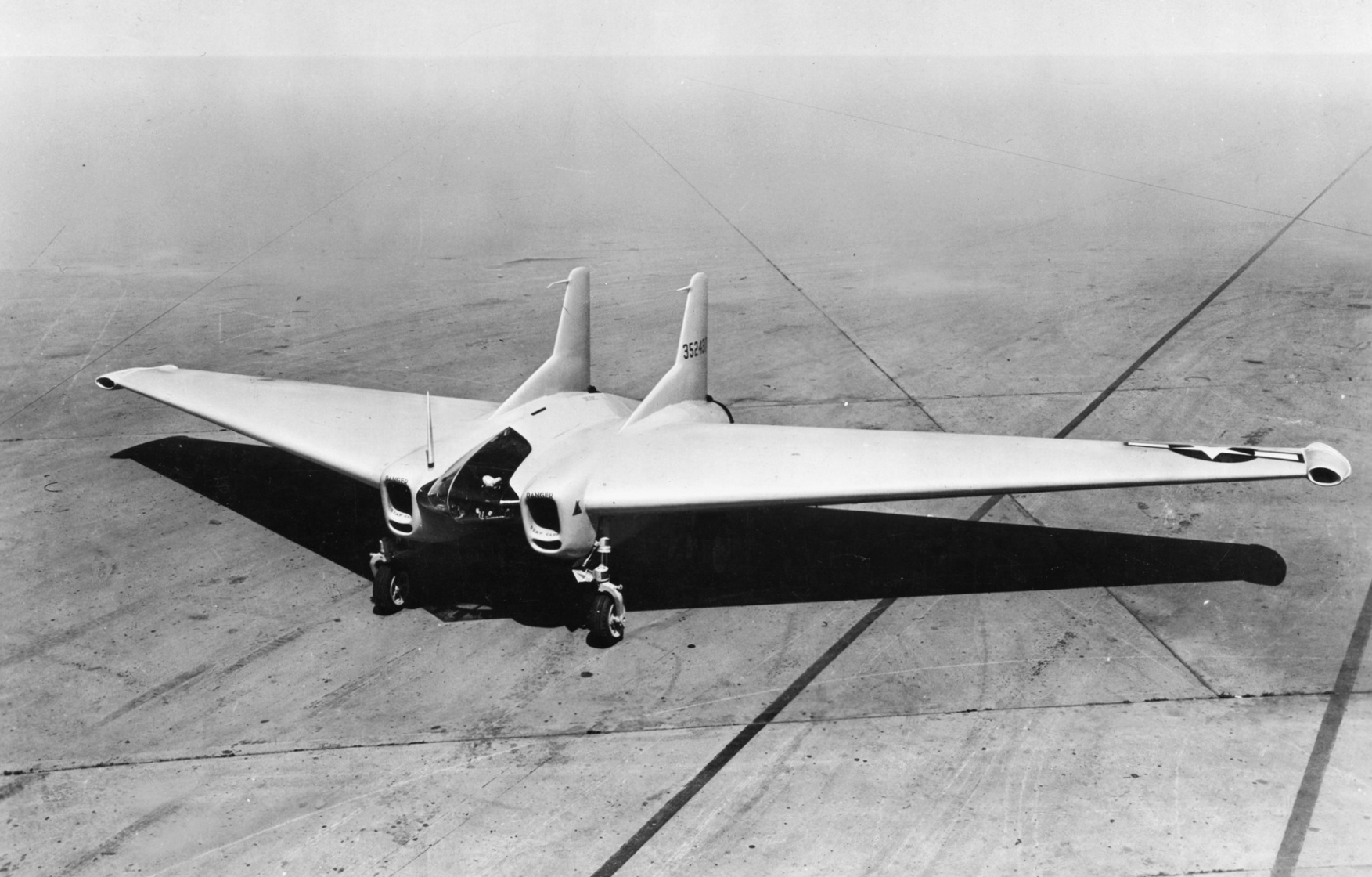

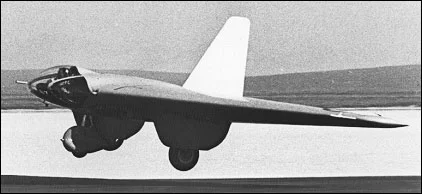

The XP-79B was paving the way for fast all-wing design aircraft.

The XP-79B was paving the way for fast all-wing design aircraft.

Eschewing the usual codified monikers, Northrop referred to his project simply as ‘The Flying Wing’. But after the first prototype had successfully taken to the skies at Burbank airport in 1929, Northrop temporarily discontinued the experiment, returning to it a decade later.

Surviving through the Great Depression by focusing solely on conventional craft, by 1939 he had established Northrop Aircraft Incorporated as the economy began to normalize. No longer beset by financial constraints and with room to experiment, Northrop revived the ‘The Flying Wing’ in early 1940, renaming it the N-1M.

N-1M, MX-324 and MX-334

Registered as an experimental civil plane with the serial number NX28311 and speedily built from wood and steel tubing, the N-1M had two Lycoming power plants providing 65 horsepower which drove twin pusher propellors.

The N-1M made its maiden voyage on July 3rd 1940. At the controls was test pilot Vance Breese, who was surprised at how well it had handled in the air, and how it had equally matched the performance of other contemporary aircraft but with noticeably less thrust. Over the course of over 200 test flights, the flying wing concept was found to be viable, compelling Northrop to next think about its various military and commercial applications.

The Northrop N1-M was a futuristic looking aircraft – imagine seeing this in the 1940s! Photo credit – Sanjay Acharya CC BY-SA 4.0.

The Northrop N1-M was a futuristic looking aircraft – imagine seeing this in the 1940s! Photo credit – Sanjay Acharya CC BY-SA 4.0.

Following a slew of further related projects including the XP-56, by 1943 Northrop was working on a top-secret contract issued by USAF known only as Project 12, and busily creating two small prototypes that would have a span of just 32 feet.

These classified air vehicles were the MX-324 and the MX-334, the latter of which was a powered version of the former, and were experimental gliders which the pilot would operate in the prone position on his stomach to reduce the effects of G-force. Towed by a Lockheed P-38 after efforts to pull the plane into the air with a car had failed, the MX-324 underwent a series of assessments throughout 1943, experiencing a handful of close shaves.

On one particularly foreboding occasion pilot Harry Crosby, who had made his name as a pre-war racing pilot, was suddenly flipped upside down by the MX-324, putting him in a downward spin. Frantically working the controls, the glider did not respond to any of Crosby’s inputs.

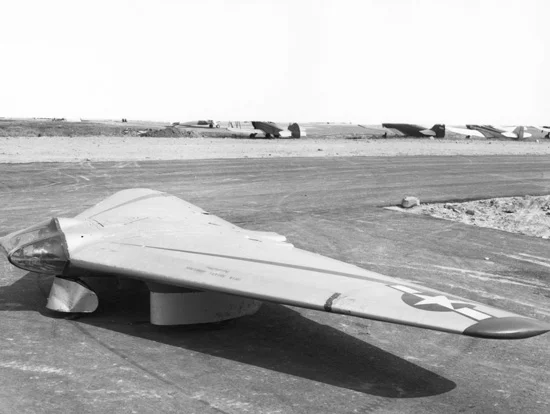

The MX-324 was an unpowered glider designed to test the concept of this wing futher.

The MX-324 was an unpowered glider designed to test the concept of this wing futher.

Eventually, the glider stopped spinning but it was still upside down and quickly approaching the ground, forcing Crosby to hurriedly climb onto the wing and parachute off.

As he floated down to earth the glider started to come towards him but luckily missed, going on to crash into the desert only a few meters from where Crosby landed.

Despite the close call, testing for the MX-334, which was fitted with an XCAL-200 rocket engine fed by monoethylaniline fuel oxidized with red-fuming nitric acid, nevertheless went ahead. Following the completion of a less eventful unpowered flight, on October 2nd 1943, the MX-334 made its first powered journey on June 23rd 1944 to become America’s first-ever rocket-propelled aircraft.

But although much had been learnt about the flying wing configuration from the MX-324 and MX-334, the design was ultimately not considered feasible by the military. Amazingly a parallel program called the XP-79, so farfetched that it bordered on the ridiculous, was viewed as a more realistic option.

The MX-334 took this concept further without the use of a vertical stabiliser.

The MX-334 took this concept further without the use of a vertical stabiliser.

XP-79

The XP-79 was unique in that it was rocket-propelled and also because its airframe was made entirely out of heavy gauge magnesium which was reinforced with steel armour plating. But the most unusual thing about it was that it was designed to knock enemy aircraft out of the air not with overwhelming firepower, but by ramming them.

The XP-79 was by no means the first attempt at this half-baked idea, for the Germans and Russians had already constructed their own rammers, often with lethal results.

Ignoring the obvious fact that any plane involved in a mid-air collision would most definitely be unable to fly afterwards, the project was taken seriously by USAF and Northrop, who assembled a single prototype.

The aircraft was made out of heavy duty materials designed for ramming.

The aircraft was made out of heavy duty materials designed for ramming.

With an empty weight of 5,840 pounds and a loaded weight of 8,670 pounds, the XP-79 was also 14 feet long, 7 feet high, and possessed a wingspan of 38 feet and a wing area of 278 square feet.

Originally anticipated to be run by a single Aerojet XCAL-200 rocket motor which could produce 1,998 pounds of thrust, manufacturing setbacks meant that it was instead powered by two Westinghouse 19-B axial flow jets each with 1,345 pounds of thrust which, awkwardly located either side of the all-wing fuselage, seriously restricted the pilot’s vision to the left and right.

Performance-wise, the XP-79 was projected to have a top speed of 525 miles per hour, a cruise speed of 479 miles per hour, an operational range of 993 miles, a rate of climb of 6,000 feet per minute, and an altitude ceiling of 40,000 feet.

The landing gear had an odd layout, being made up of two forward gear legs and two rear gear legs that retracted into its wings, while the vertical fin was wire-braced. Another curious feature was that the pilot, encased in an unpressurized cockpit that could be accessed via an overhead hatch, was to operate it lying down on his stomach in the prone position, placing his head into an acrylic plastic windshield protected by a layer of armoured glass.

A close up of the XP-79B.

A close up of the XP-79B.

Cocooned inside, the pilot controlled the pitch and roll of the XP-79 with a cross-bar control rod while foot pedals were used for braking, and on the plane itself elevons and air intakes at the wingtips enabled lateral control.

In order to get inside, the pilot had to rather embarrassingly scramble up from the trailing edge on his belly and enter the hatch head-first, with his dangling legs following in shortly after.

The planned operation was breathtakingly silly. A typical mission would start with it being blasted off with the assistance of JATO packs just as a fleet of enemy bombers was approaching. Next, the XP-79 was to ascend to 40,000 feet, and flying above the formation was to dip down and try to cut off the tail or wing of a bomber.

Many USAF officials had justifiably strong reservations about the whole project, and so it was requested that the XP-79 also to be installed with four 12.7 mm Browning M3 machine guns each with 250 rounds of ammo, situated on the wing-centre section.

Crash

In January 1943 a contract was awarded approving the construction of 3 units, but in the end due to developmental problems with some of the rocket engines only one XP-79 was ever made, and it was to have a very short lifespan.

Unfortunately the XP-79B crashed killing the pilot.

Unfortunately the XP-79B crashed killing the pilot.

Painted white and given the serial number 43-52537, the XP-79 was loaded onto a truck hidden by a canvas sheet and transferred to Muroc Dry Lake for flight assessment. Pilot Harry Crosby, who was planning to retire to his farm in California afterwards, would again be at the helm.

On September 12th 1945 it accelerated down the runway narrowly avoiding an Army fire truck that had unwittingly moved into its pathway. Lifting off into the air, the craft climbed to 10,000 feet at 400 miles per hour before Crosby attempted to make a turning maneuver around 15 minutes in. The operation however, went terribly wrong when the XP-79 suddenly entered into a nose-down spin in the same fashion as the MX-324.

Once again Crosby tried to bring it back under control but to no avail, for like the MX-324 it was also unresponsive and seemingly had a mind of its own. Crosby swiftly climbed out of the rapidly descending plane and jumped out, but before he could activate his parachute he was struck by the rotating wing and killed instantly.

When the XP-79 smashed into the ground it exploded into a raging fire made even hotter by burning magnesium. Safe to say, USAF or Northrop never again pursued such a harebrained scheme.

If you like this article, then please follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Specifications

Crew: 1

Length: 13.98 ft (4.26 m)

Wingspan: 37.99 ft (11.58 m)

Height: 7.58 ft (2.31 m)

Empty weight: 5,842 lb (2,650 kg)

Gross weight: 8,669 lb (3,932 kg)

Powerplant: 2 × Westinghouse 19B axial flow turbojet, 1,150 lbf (5.1 kN) thrust each (for the XP-79B model)

Maximum speed: 547 mph (880 km/h, 475 kn)

Range: 993 mi (1,598 km, 863 nmi)

Service ceiling: 40,000 ft (12,000 m)

Rate of climb: 4,000 ft/min (20 m/s)

News

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering Perched precariously on the cliffs of Mount Heng in Shanxi Province, China, the Hanging Temple, also known as Xuankong Temple, Hengshan Hanging Temple, or Hanging Monastery, is an architectural…

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets The “Willendorf Venus” stands as one of the most revered archaeological treasures from the Upper Paleolithic era. Discovered in 1908 by scientist Johann Veran near Willendorf, Austria, this small yet profound…

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts New archaeological research has uncovered intriguing insights into the ritual practices of the ancient Maya civilization. The focus of this study is a ceremonial offering found beneath the sediment…

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins The history of agricultural innovation is a fascinating journey that spans thousands of years, and one of the earliest known agricultural machines is the threshing sledge. Recently, a groundbreaking study…

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits In a remarkable discovery that has captured the attention of archaeologists and historians alike, a 7.5-foot-long iron sword was unearthed from a 1,600-year-old burial mound in Nara, Japan. This oversized weapon,…

The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots

Experimental The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots The Inflatoplane from Goodyear was an unconventional aircraft developed by the Goodyear Aircraft Company, a branch of the renowned Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, also famed for the Goodyear…

End of content

No more pages to load