Germany’s Gigantic Flak Tower Bunkers

German flak towers, or “Flaktürme,” were monumental concrete fortresses constructed during the Second World War across various cities within Nazi Germany and its occupied territories. These structures served a dual purpose: they were air defense platforms equipped with anti-aircraft artillery to counter Allied bombing raids, and they also functioned as air raid shelters for civilians.

These gigantic buildings were armed to the teeth with some of the most powerful anti-aircraft guns of the war, and were completely self-sufficient, complete with hospitals, food, water, power generators and more.

Some bunker personnel estimated that they could hold off for about a year, even if the surrounding city had been taken! For that reason, they were some of final areas of resistance at the war’s end.

Background

The Allies, particularly the British Royal Air Force (RAF) and the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), escalated their strategic bombing campaign against Nazi Germany throughout the war. The goal was twofold: to dismantle the German war machine by targeting industrial and military infrastructures and to erode civilian morale by bombing urban centers.

This relentless aerial onslaught highlighted the urgent need for effective air defense systems to protect vital targets and civilian populations.

In response to this threat, Adolf Hitler ordered the construction of flak towers. These towers were to serve as formidable anti-aircraft defense installations, capable of repelling enemy bombers and shielding cities from aerial attacks.

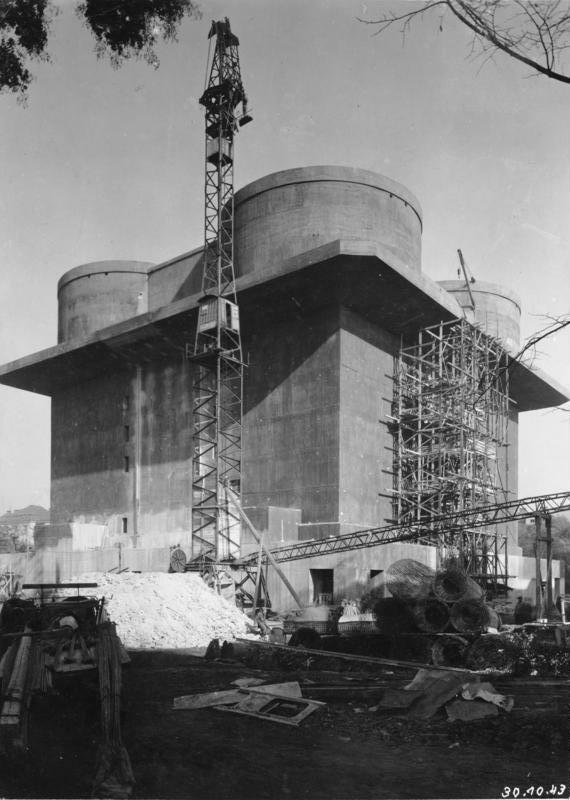

Flak Tower during construction.

Flak Tower during construction.

The concept was proposed as part of a larger strategy to fortify the Reich against the increasing might of the Allied air forces. Flak towers were envisioned not only as platforms for heavy anti-aircraft guns but also as shelters for civilians.

The design and deployment of flak towers were influenced by the experiences of the Luftwaffe, the German air force, in defending the Reich. Early in the war, the Luftwaffe was primarily offensive, but as the tide turned, it found itself on the defensive, struggling to counter the overwhelming air superiority of the Allies.

The traditional anti-aircraft batteries, dispersed to defend cities, industrial and military areas, were proving insufficient to stop or significantly deter the bombing raids. The flak towers, with their high-density anti-aircraft guns and radar-guided fire control systems were meant to throw up a much greater volume of fire over particularly important areas.

Moreover, the flak towers were to serve a secondary, equally critical role as bomb shelters for civilians. The psychological impact of the bombing raids on the German population was profound, with widespread fear, anxiety, and the disruption of daily life becoming commonplace.

By providing refuge to thousands of civilians during air raids, the flak towers aimed to bolster civilian morale, offering a place of safety during attacks. This was an attempt by Germany attempt to maintain public support and demonstrate its commitment to the protection of its people, even as the war turned increasingly against it.

Design and Construction

Towers were constructed in Berlin, Hamburg, and Vienna, with each city’s installations tailored to its specific defensive needs and urban layout. They were built to withstand direct hits from the heaviest bombs of the era, all the while providing a 360 degree field of fire.

Constructed out of reinforced concrete, their walls and ceilings could be up to 5 meters thick, a feature that made them virtually impervious to the bombs of the time. This incredible thickness of the concrete used ensured that the structures could absorb and withstand the shock of aerial bombings without compromising their integrity.

The design also included internal compartments and corridors that were shock-resistant, protecting both the military personnel operating the anti-aircraft guns and the civilians seeking shelter within.

Flakturm IV in Hamburg, Germany.

Flakturm IV in Hamburg, Germany.

Each complex typically consisted of G-towers (Gefechtsturm) for combat operations and a smaller L-tower (Leitturm) that served as a command and observation post that guided the G-tower’s fire. The G-towers were armed with a variety of anti-aircraft (AA) guns, ranging from 2 cm cannons to 12.8 cm guns capable of reaching high-altitude bombers.

The 12.8 cm FlaK 40 guns were some of the most powerful AA guns of the war. They were very large pieces, making them unsuitable for mobile ground operations, but were perfect in static positions on top of flak towers.

These guns were capable of throwing a 60 lb projectile up to a maximum altitude of 48,000 ft! Some were mounted in twin mounts, known as 12.8 cm Flakzwilling 40/2s. These could fire up to 20 rounds a minute, although they were available in much lower numbers and only used some flak towers.

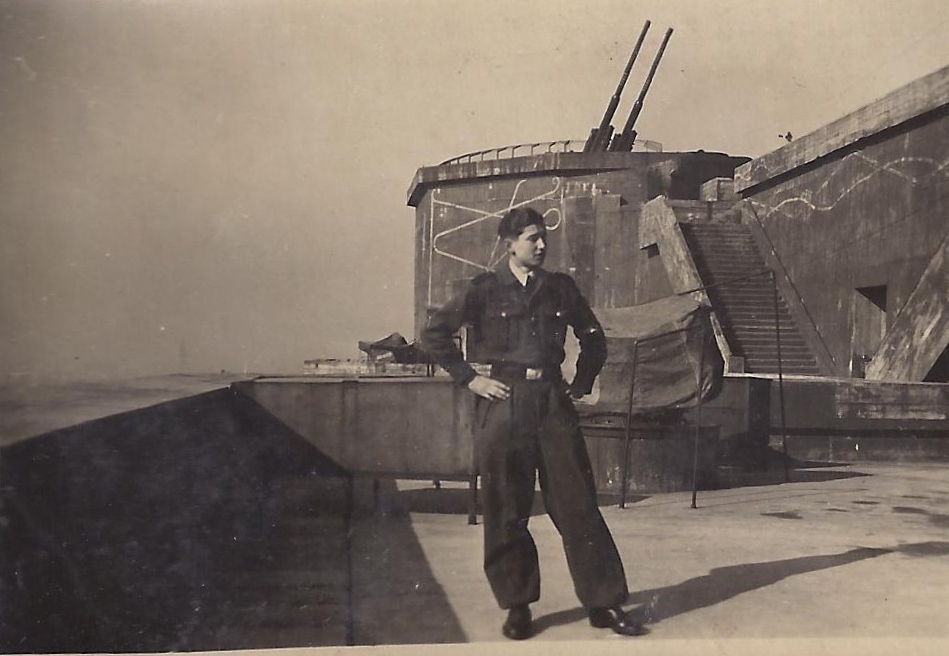

Dual-mounted 12.8 cm FlaK 40s can be seen in the background of this image on the Humboldthain tower.

Dual-mounted 12.8 cm FlaK 40s can be seen in the background of this image on the Humboldthain tower.

These towers also housed radar installations and searchlights to track and target incoming aircraft, making them highly effective defensive positions.

The construction of the flak towers began in 1940 and was an enormous logistical challenge, requiring significant resources and labor in a time of war. The speed at which they were built is remarkable, with some towers being completed in as little as six months.

This rapid construction was achieved through round-the-clock work shifts and the use of prefabricated materials wherever possible. To ensure deliveries of raw materials were made, civilian rail networks were commandeered where needed.

The G and L towers at Arenbergpark in Vienna. Image by Kasa Fue CC BY-SA 4.0.

The G and L towers at Arenbergpark in Vienna. Image by Kasa Fue CC BY-SA 4.0.

The strategic placement of flak towers within cities was another critical aspect of their design. They were situated to maximize coverage against aerial attacks, with their fields of fire overlapping to create a dense anti-aircraft defense network. This placement also considered the towers’ role as shelters, ensuring that civilians could access them quickly during air raids.

Inside, provisions were made to accept thousands of civilians if required. The towers were completely self-sufficient, with their own power generation, medical facilities, food, water and ammunition. They were even made gas proof.

Crews open one of the armored vault doors on the roof of a flak tower. These vaults weighed 72 tons.

Crews open one of the armored vault doors on the roof of a flak tower. These vaults weighed 72 tons.

Locations

Flak towers were erected in Berlin, Hamburg, and Vienna. Each city had multiple flak tower complexes, strategically positioned to provide overlapping fields of fire and maximize coverage against incoming bombers.

Berlin, the Reich’s capital and heart of Nazi Germany, was naturally a prime target for Allied bombers. To defend the city, three flak tower complexes were constructed: the Zoo Tower in the Tiergarten, the Friedrichshain Tower in the park of the same name, and the Humboldthain Tower in the Humboldthain Park.

The Zoo Tower, in particular, became one of the most famous flak towers of the war, serving as a last bastion of defense during the Battle of Berlin in 1945. This tower was the first built, completed in 1941, after the RAF’s first attack on Berlin. This attack was embarrassing for the Nazi high command, and so the towers in Berlin were not only military installations but also symbols of strength to comfort their population.

The tower at Augarten in Vienna is one of the most visually striking. Some may recognise this tower from the game Medal of Honor: Airborne. Image by Gugerell.

The tower at Augarten in Vienna is one of the most visually striking. Some may recognise this tower from the game Medal of Honor: Airborne. Image by Gugerell.

Hamburg, one of Germany’s most important port cities, was crucial for the war effort due to its shipbuilding yards and industrial facilities. The city was defended by three flak tower complexes.

They were positioned to protect the industrial heartland and the port facilities, vital for German naval operations and the supply chain. The sheer resilience of these structures was demonstrated here, as they withstood some of the most intense bombings of the war, continuing to operate amidst the firestorm that engulfed the city.

Flakturm IV in Hamburg is one of the largest of the towers, and one of the largest above-ground bunkers ever built. It held eight 12.8 cm guns, and held up to 25,000 civilians.

Heiligengeistfeld tower in Hamburg, better known as Flakturm IV. Image by Solari CC BY-SA 3.0.

Heiligengeistfeld tower in Hamburg, better known as Flakturm IV. Image by Solari CC BY-SA 3.0.

Vienna had the most flak towers, with six in total, being constructed later in the war. The city, with its rich cultural heritage and historical significance, was equipped with flak towers to defend against Allied air raids, but they also served a secondary purpose: the preservation of art and cultural treasures.

The towers in Vienna were used to store valuable artworks and artifacts, protecting them from destruction. In the aftermath of the war, the flak towers’ sheer size and the strength of their construction posed significant challenges for demolition, leading many to be repurposed or integrated into the urban landscape.

The command tower at Augarten in Vienna. This directed fire for the nearby G-tower. Image by PaulT (Gunther Tschuch) CC BY-SA 4.0.

The command tower at Augarten in Vienna. This directed fire for the nearby G-tower. Image by PaulT (Gunther Tschuch) CC BY-SA 4.0.

Flak Tower Effectiveness

These imposing structures were not only a technical response to the Allied bombing campaigns but also a strategic tool aimed at bolstering morale among the German populace. Their presence, however, arguably was more useful as air raid shelters than it was for AA fire.

Of course, the flak towers were formidable anti-aircraft platforms. Their construction allowed for an unprecedented concentration of anti-aircraft artillery in key strategic locations.

Equipped with heavy flak guns capable of reaching high-altitude targets, these towers significantly increased the defensive capabilities of the cities in which they were located. The strategic positioning of the towers allowed for overlapping fields of fire, creating dense anti-aircraft zones that forced Allied bombers to adjust their tactics.

The towers could defend against both high and low flying aircraft.

The towers could defend against both high and low flying aircraft.

In some cases, bombers were compelled to fly at higher altitudes to evade the intense flak, which, while reducing the accuracy of their bombing runs, did not entirely negate the threat. Moreover, the towers’ resilience to bombing—owing to their thick reinforced concrete walls—meant they remained operational throughout the war.

In cities that were subjected to frequent and devastating air raids, the towers served as morale boosters. For many civilians, the towers offered refuge during bombings in their vast shelters that could accommodate thousands.

These shelters were not mere spaces of refuge but were also equipped with amenities such as hospitals, schools, and even entertainment facilities.

Crews work on top of a flak tower.

Crews work on top of a flak tower.

However, the effectiveness of the flak towers in achieving their intended military and psychological objectives is a subject of historical debate. While they undeniably posed a significant challenge to Allied bombers and contributed to the defense of key urban centers, their impact on the overall course of the war was limited.

The resources required for their construction—vast amounts of labor, materials, and weaponry—were immense, leading some historians to question whether these resources could have been more effectively allocated to other aspects of the war effort.

Moreover, the strategic bombing campaign, despite being hindered by the towers, ultimately achieved its objective of crippling Germany’s war machinery and infrastructure. The flak towers, for all their might and symbolism, could not prevent the eventual downfall of the Nazi regime.

This flak tower at Humboldthain in Berlin was only partially demolished. Half was buried, but the inside is accessible today. Image by Kasa Fue CC BY-SA 4.0.

This flak tower at Humboldthain in Berlin was only partially demolished. Half was buried, but the inside is accessible today. Image by Kasa Fue CC BY-SA 4.0.

Post-War

Unfortunately for the cities that hosted them, the end of the war did not simply render these towers obsolete; it left behind a complex problem of what to do with such massive, indestructible fortresses.

Constructed from reinforced concrete with walls up to 3.5 meters thick, these towers were designed to withstand the most severe bombing raids. This made them almost impervious to demolition efforts in the aftermath of the war.

Some were demolished, like the Zoo Tower in Berlin, but it often took months and proved to be prohibitively expensive and dangerous, leading to the decision to leave most of the structures standing.

Friedrichshain bunker in Berlin after an attempt was made to demolish it.

Friedrichshain bunker in Berlin after an attempt was made to demolish it.

As the immediate post-war years gave way to reconstruction and redevelopment, and without any practical way of removing them, some cities found innovative ways to repurpose the flak towers. In Vienna, for example, one of the towers was transformed into the Haus des Meeres, a public aquarium that now serves as a popular attraction, seamlessly integrating a symbol of war into the fabric of civilian life.

In Hamburg, a flak tower has been converted into an energy storage facility, while the tower at Arenbergpark in Vienna has been repurposed into a climbing wall.

Where repurposing has not been feasible, some flak towers have been preserved as historical monuments. The G-Tower at Humboldthain in Berlin, for example, was partially demolished but can be toured today.

Heiligengeistfeld tower during roof renovations. Image by Hinnerk11 CC BY-SA 4.0.

Heiligengeistfeld tower during roof renovations. Image by Hinnerk11 CC BY-SA 4.0.

But the most dramatic transformation has been to Flakturm IV at Heiligengeistfeld in Hamburg. This 38 meter tall structure was used as emergency housing after the war, and then in the 1990s was used as a media center.

More recently, a large construction was built on the roof of Flakturm IV that contains gardens, parks, restaurants, a hotel and sports facilities.

News

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering

The Hanging Temple: China’s 1,500-Year-Old Cliffside Marvel of Faith and Engineering Perched precariously on the cliffs of Mount Heng in Shanxi Province, China, the Hanging Temple, also known as Xuankong Temple, Hengshan Hanging Temple, or Hanging Monastery, is an architectural…

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets

The Willendorf Venus: A 30,000-Year-Old Masterpiece Reveals Astonishing Secrets The “Willendorf Venus” stands as one of the most revered archaeological treasures from the Upper Paleolithic era. Discovered in 1908 by scientist Johann Veran near Willendorf, Austria, this small yet profound…

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts

Unveiling the Maya: Hallucinogens and Rituals Beneath the Yucatán Ball Courts New archaeological research has uncovered intriguing insights into the ritual practices of the ancient Maya civilization. The focus of this study is a ceremonial offering found beneath the sediment…

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins

Uncovering the Oldest Agricultural Machine: The Threshing Sledge’s Neolithic Origins The history of agricultural innovation is a fascinating journey that spans thousands of years, and one of the earliest known agricultural machines is the threshing sledge. Recently, a groundbreaking study…

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits

Nara’s Ancient Sword: A 1,600-Year-Old Protector Against Evil Spirits In a remarkable discovery that has captured the attention of archaeologists and historians alike, a 7.5-foot-long iron sword was unearthed from a 1,600-year-old burial mound in Nara, Japan. This oversized weapon,…

The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots

Experimental The Inflatable Plane, Dropped Behind the Lines for Downed Pilots The Inflatoplane from Goodyear was an unconventional aircraft developed by the Goodyear Aircraft Company, a branch of the renowned Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, also famed for the Goodyear…

End of content

No more pages to load